09.07.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release, Theory in Biodiversity Science

The right mix and planting pattern of trees enhance forest productivity and services

More08.07.2025 | Biodiversity and People, iDiv, Media Release, Research

Study shows people perceive biodiversity

More02.07.2025 | Blog Post, iDiv

Context matters: Plant diversity affects soil carbon storage differently across ecosystems

More19.06.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, UFZ-News

The role of researchers in politically charged debates

More19.06.2025 | iDiv, Media Release

The seemingly impossible reproduction of dogroses hinges on a centromere trick

More16.06.2025 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, Science-Policy

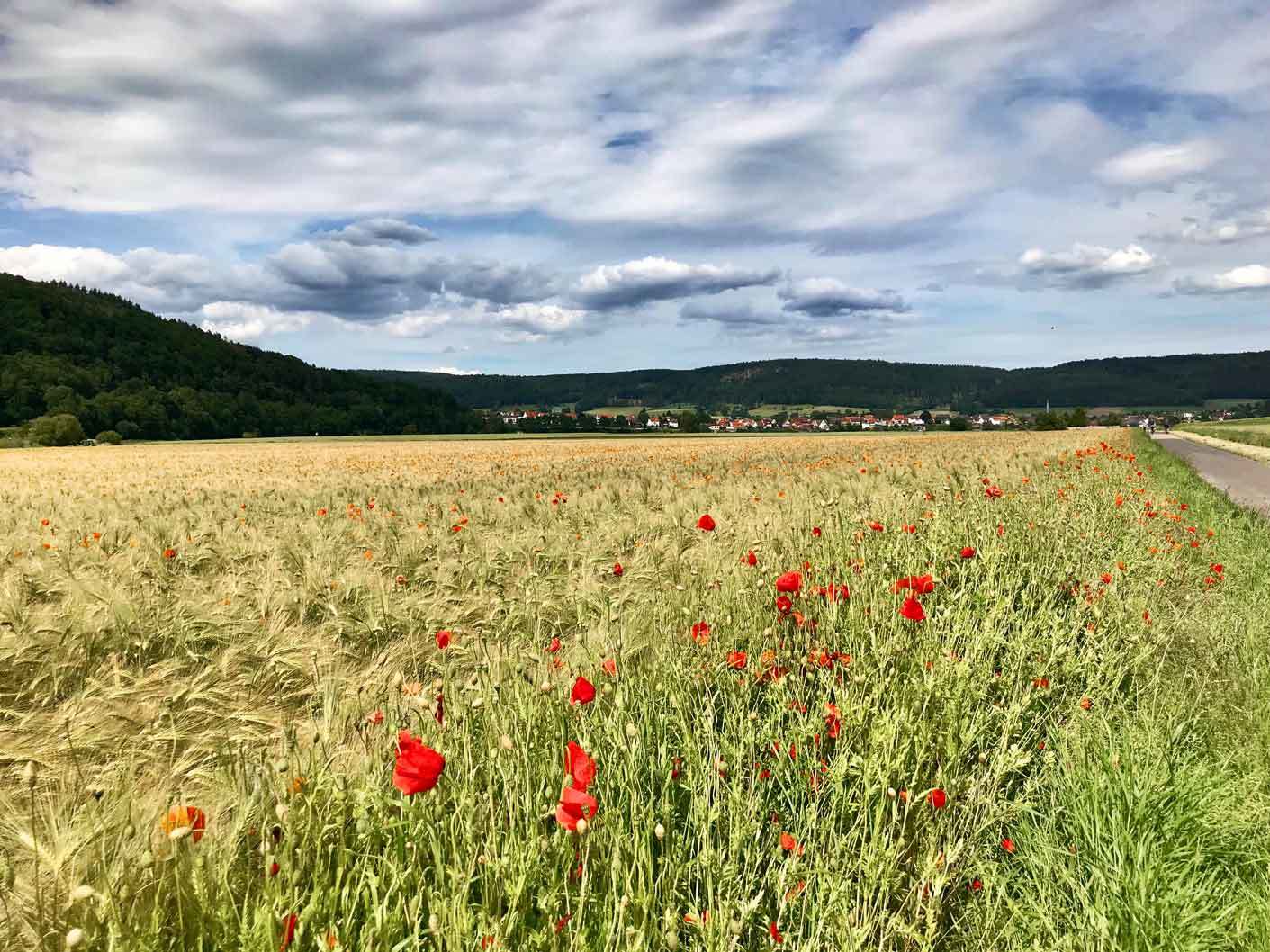

Integrating rewilding into intensively used farmland

More10.06.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release

iDiv Research Group Experimental Interaction Ecology honoured with “Best Research Environment” award

More02.06.2025 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv, Media Release, Research, Science-Policy

Preserving the past, protecting the future: Historic village water tanks provide a lifeline for amphibians

More26.05.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, MLU News

Study on knowledge transfer: How the “Gollum effect” hinders research and careers

More21.05.2025 | Blog Post, iDiv, Science-Policy

The EU’s Nature Restoration Regulation: How iDiv supports Europe’s path toward unified implementation

More

15.05.2025 | iDiv, Media Release

ESA’s 2025 Cooper Award Honors Groundbreaking Work on Taxonomic Harmonization in Biodiversity Research

More05.05.2025 | Biodiversity and People, Media Release

Citizen Science project FLOW receives new funding

More30.04.2025 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release

From the front garden to the continent: Why biodiversity does not increase evenly from small to large

More29.04.2025 | iDiv, iDiv Members

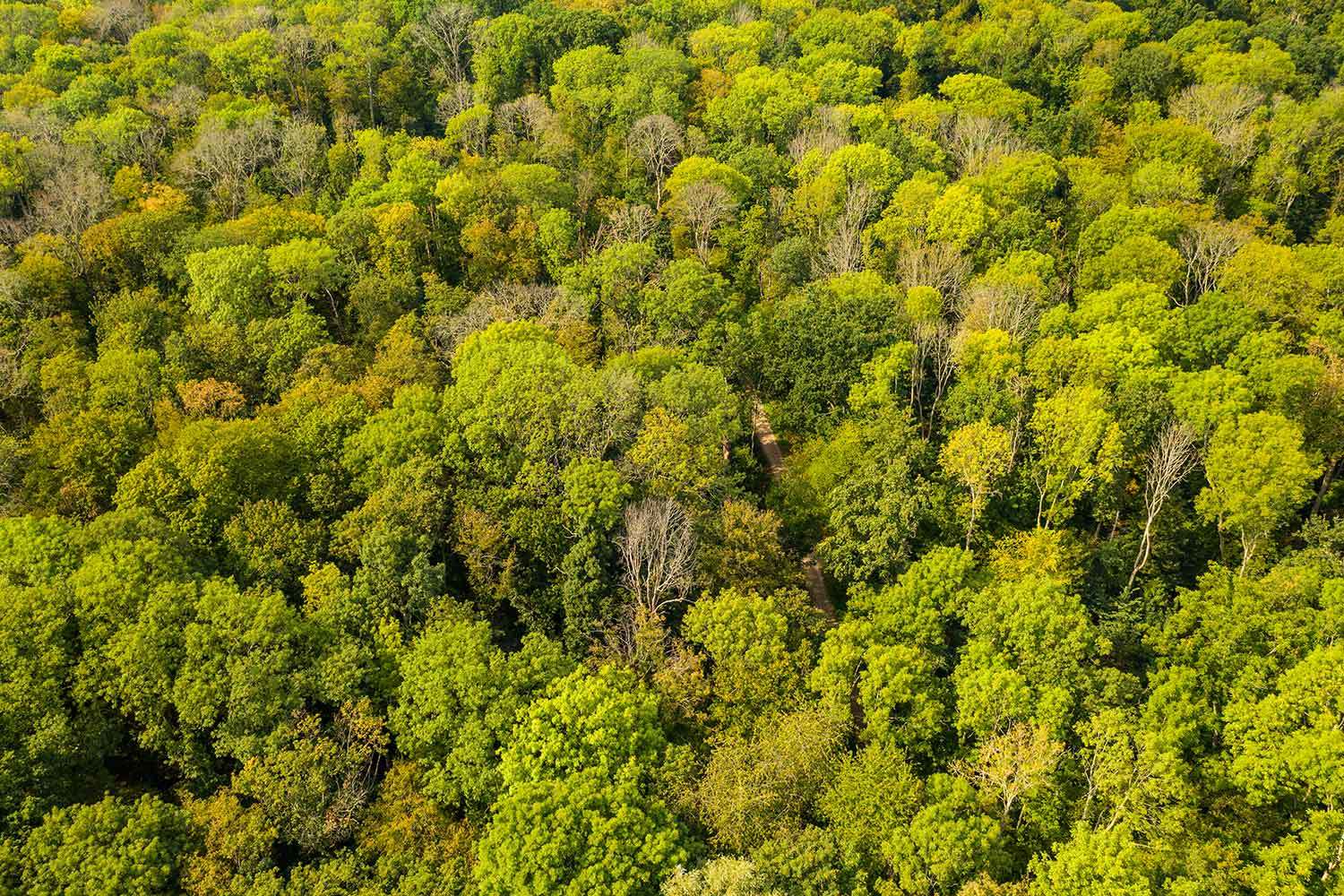

What microorganisms in tree crowns reveal about forest biodiversity

More17.04.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, Research

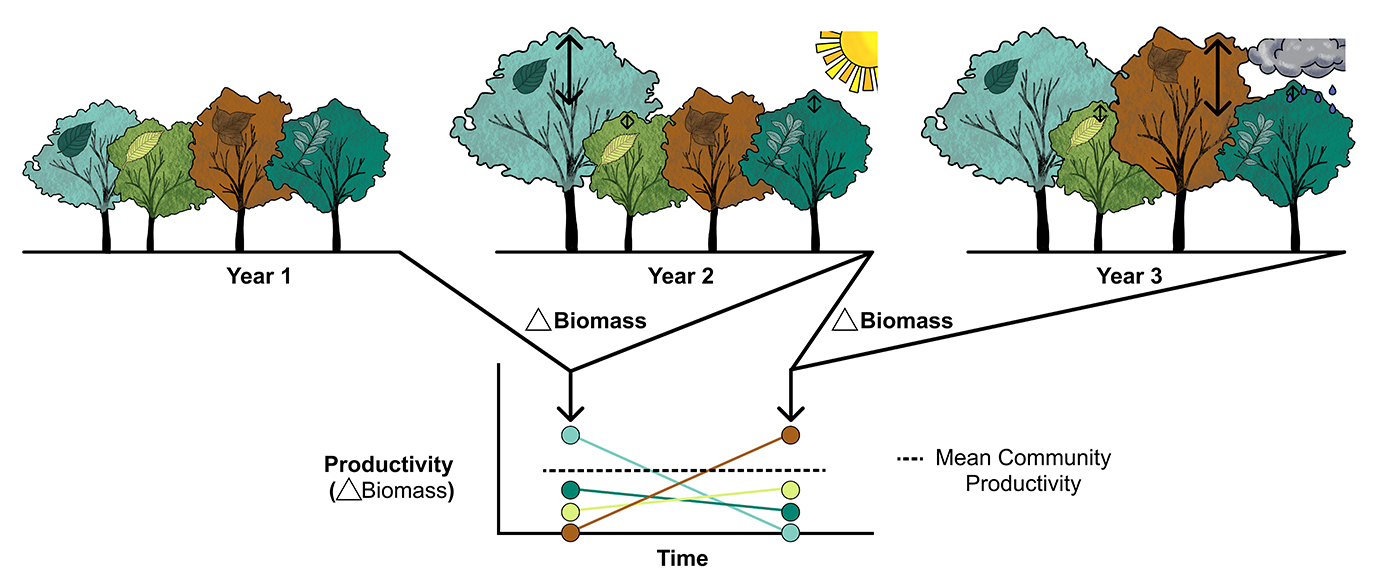

Nutrients strengthen link between precipitation and plant growth, study finds

Global analysis reveals a stronger biomass growth when key nutrients are not limiting.

More16.04.2025 | iDiv, iDiv Members, Research

Experiment in Leipzig’s floodplain forest: Using tree mortality to support oak regeneration

More11.04.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, Theory in Biodiversity Science

“Internet of nature” helps researchers explore the web of life

More10.04.2025 | Blog Post

Striving for Gender Equity in Academia: Insights from the iDiv Female Scientists Initiative

More03.04.2025 | iDiv, Media Release

New podcast “Inside Biodiversity”

Inside Biodiversity is a new podcast hosted by iDiv.

More03.04.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, Species Interaction Ecology

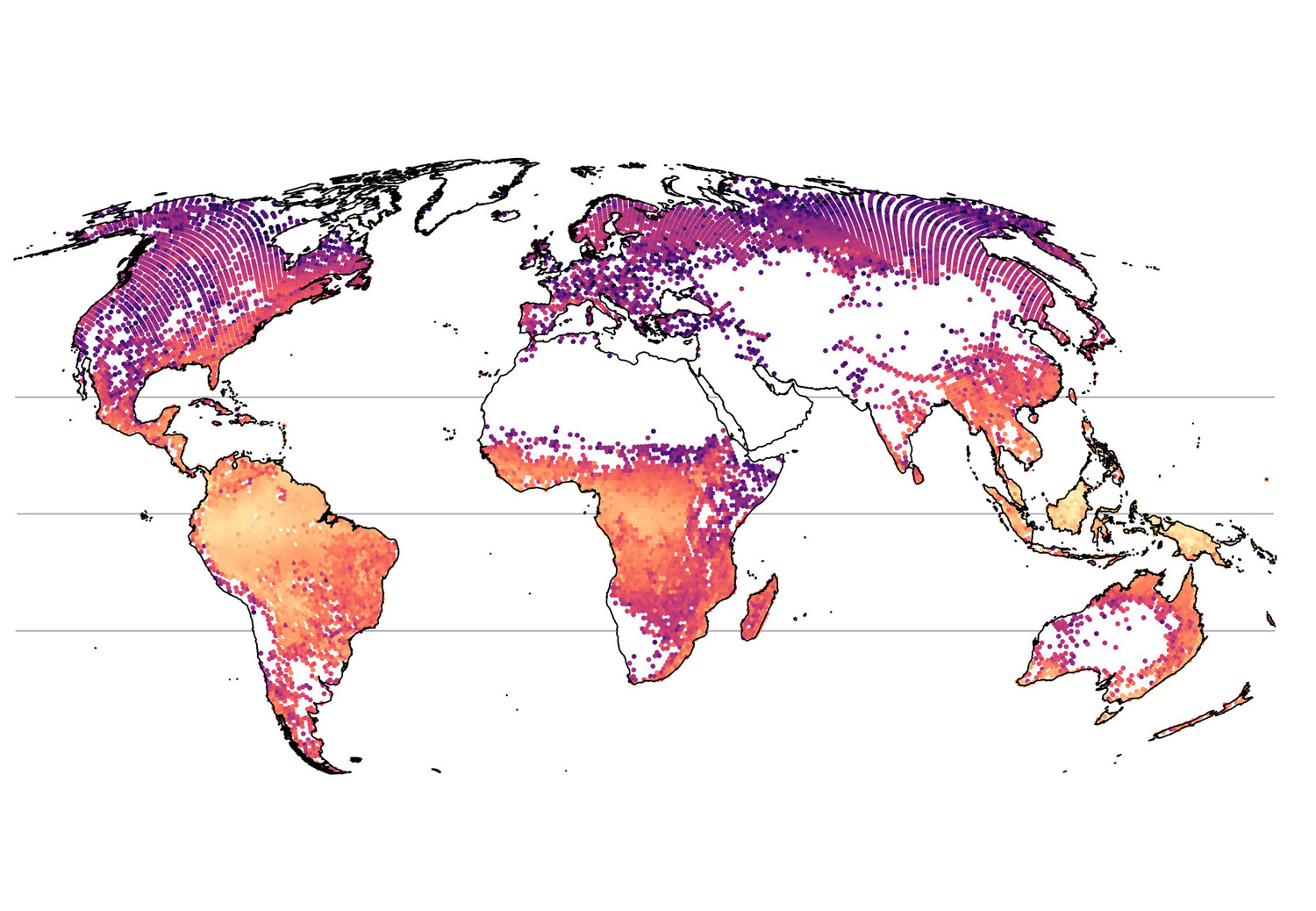

Dark Diversity Reveals Global Impoverishment of Natural Vegetation

Nature study shows that the potential occurrence of plant species is significantly higher

More27.03.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, sDiv

Study shows global seed plant distribution over millions of years

More26.03.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, Theory in Biodiversity Science

How elephants plan their journeys: New study reveals energy-saving strategies

More24.03.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv Members, Media Release

Tree diversity helps reduce heat peaks in forests

More20.03.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, Research

Resource-efficient tree species grow faster under real conditions, study shows

More13.03.2025 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, Research

New study refutes habitat fragmentation claim

More11.03.2025 | Blog Post, iDiv, sDiv

Unraveling the Secrets of Grassland Biodiversity in Ukraine

How an sDiv collaboration helped reunite Ukrainian scholars scattered across Europe due to the war and provided them with an environment of stability, focus, and scientific exchange.

More05.03.2025 | iDiv, Media Release, Research

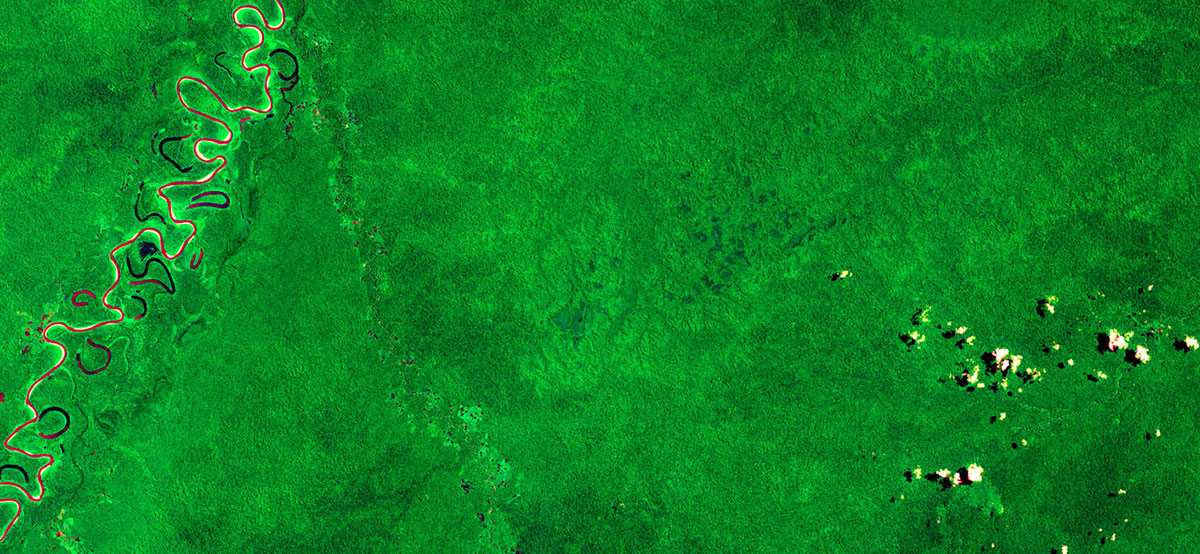

Satellite image analysis new insight into tropical forests

New Nature paper: satellite images from space are allowing scientists to delve deeper into the individual functions of different tropical forest canopies.

More05.03.2025 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv, Media Release

The future of nature conservation in Europe

An international research team is pioneering an approach to European conservation, integrating biodiversity as a solution to environmental challenges.

More27.02.2025 | Blog Post, sDiv

50,000 sDiv citations – 12 years of excellence in biodiversity research

More19.02.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release

Translating Soil Biodiversity receives Grüter Prize

The Werner and Inge Grüter Foundation’s 2025 Award for Science Communication goes to ‘Translating Soil Biodiversity’.

More13.02.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release, Research, sDiv

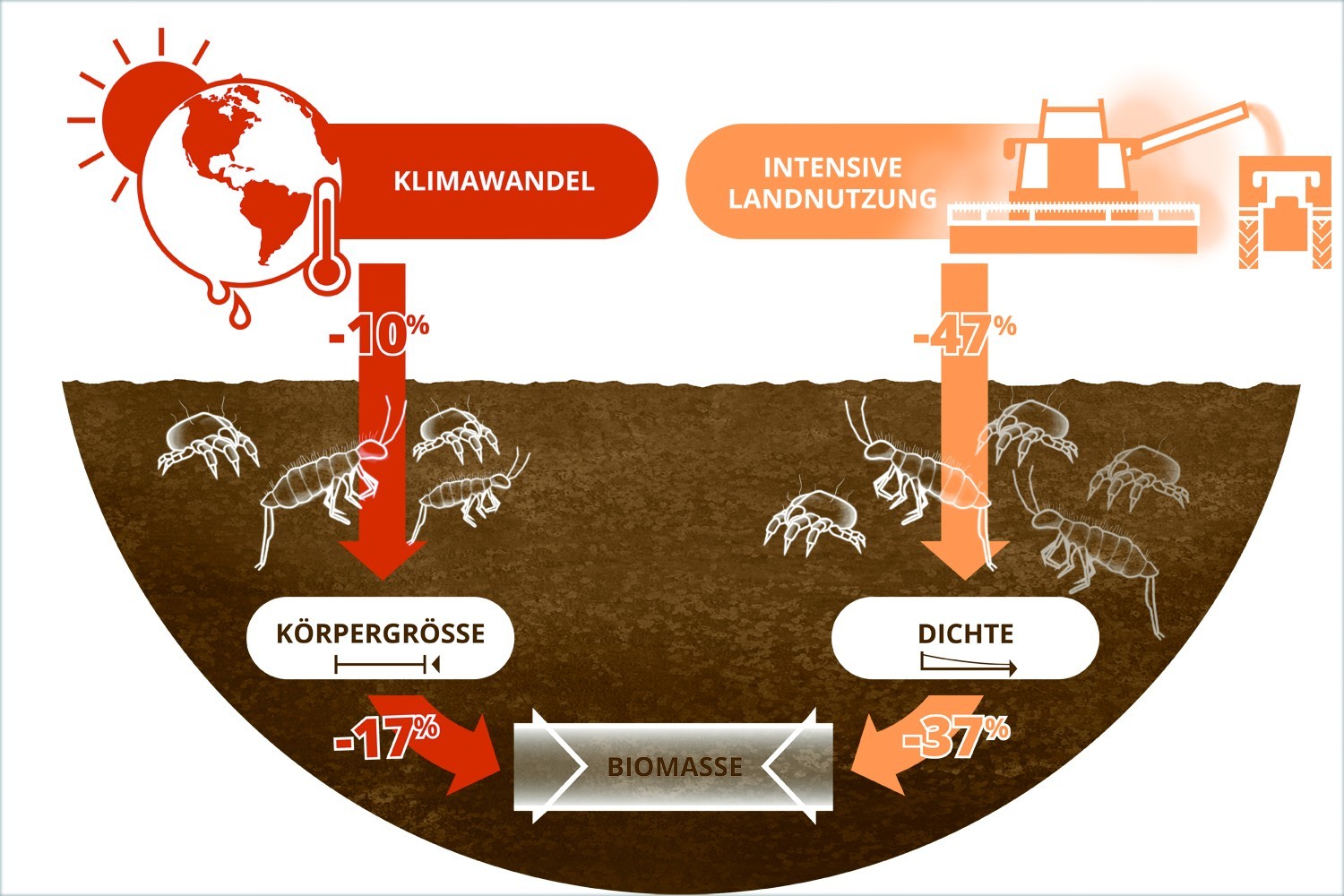

Hidden engineers help shape terrestrial ecosystems

A new paper in Nature shows how soil invertebrates’ engineering effects drive global ecosystem functions.

More

30.01.2025 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release

Transfer prize for Translating Soil Biodiversity project

The team behind the ‘Translating Soil Biodiversity’ project at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) has been awarded the Transfer Prize of Leipzig University.

More

29.01.2025 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, Theory in Biodiversity Science

Climate change reshuffles species like a deck of cards

A new study found that biodiversity has changed faster in locations where warming or cooling was faster

More

15.01.2025 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Research

New technique by scientists reveals genetic ties within animal populations

More13.01.2025 | Biodiversity and People, iDiv, Media Release

Perspective: Tree crops key to advancing Sustainable Development Goals

More09.01.2025 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv Members, Media Release

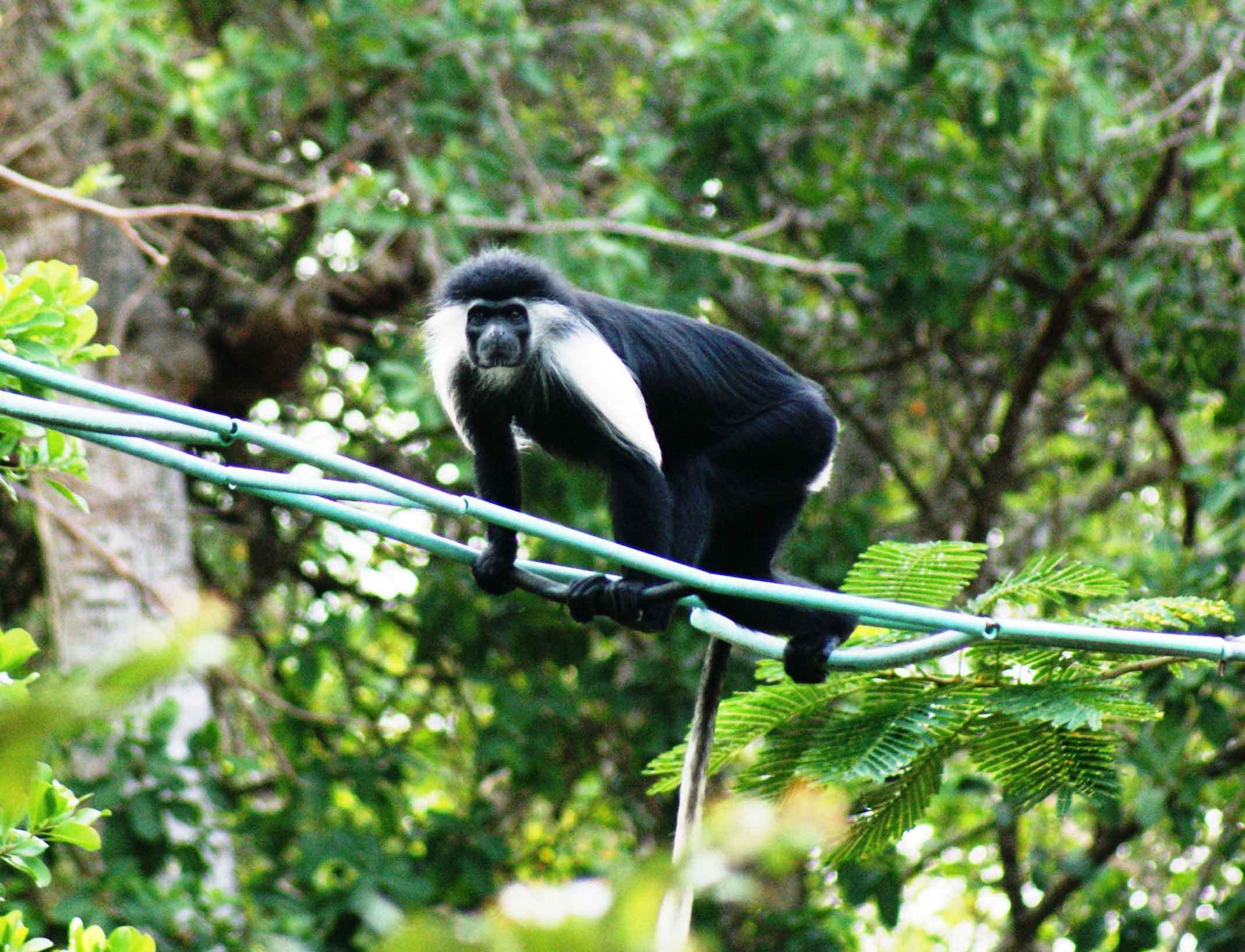

Chimpanzees are genetically adapted local habitats and infections such as malaria

Chimpanzees bear genetic adaptations that help them thrive in their different forest and savannah habitats, some of which may protect against malaria

More

18.12.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Soil Biodiversity and Functions

Anton Potapov receives ERC Consolidator Grant

The grant will fund the iDiv member’s research project CARBONWEB with around two million euros

More

04.12.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, TOP NEWS

Henrique Pereira elected member of the Academia Europaea

Membership honours individuals who have demonstrated “sustained academic excellence”

More04.12.2024 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Survival Strategies of Tiny Soil Microbes Unravelled

New Nature paper has revealed how soil microbes are impacted by extreme weather events, offering new insights into the risks posed by climate change.

More03.12.2024 | iDiv Members, MLU News, TOP NEWS

Ecosystems: new study questions common assumption about biodiversity

Plant species can fulfil different functions within an ecosystem, even if they are closely related to each other.

More21.11.2024 | Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

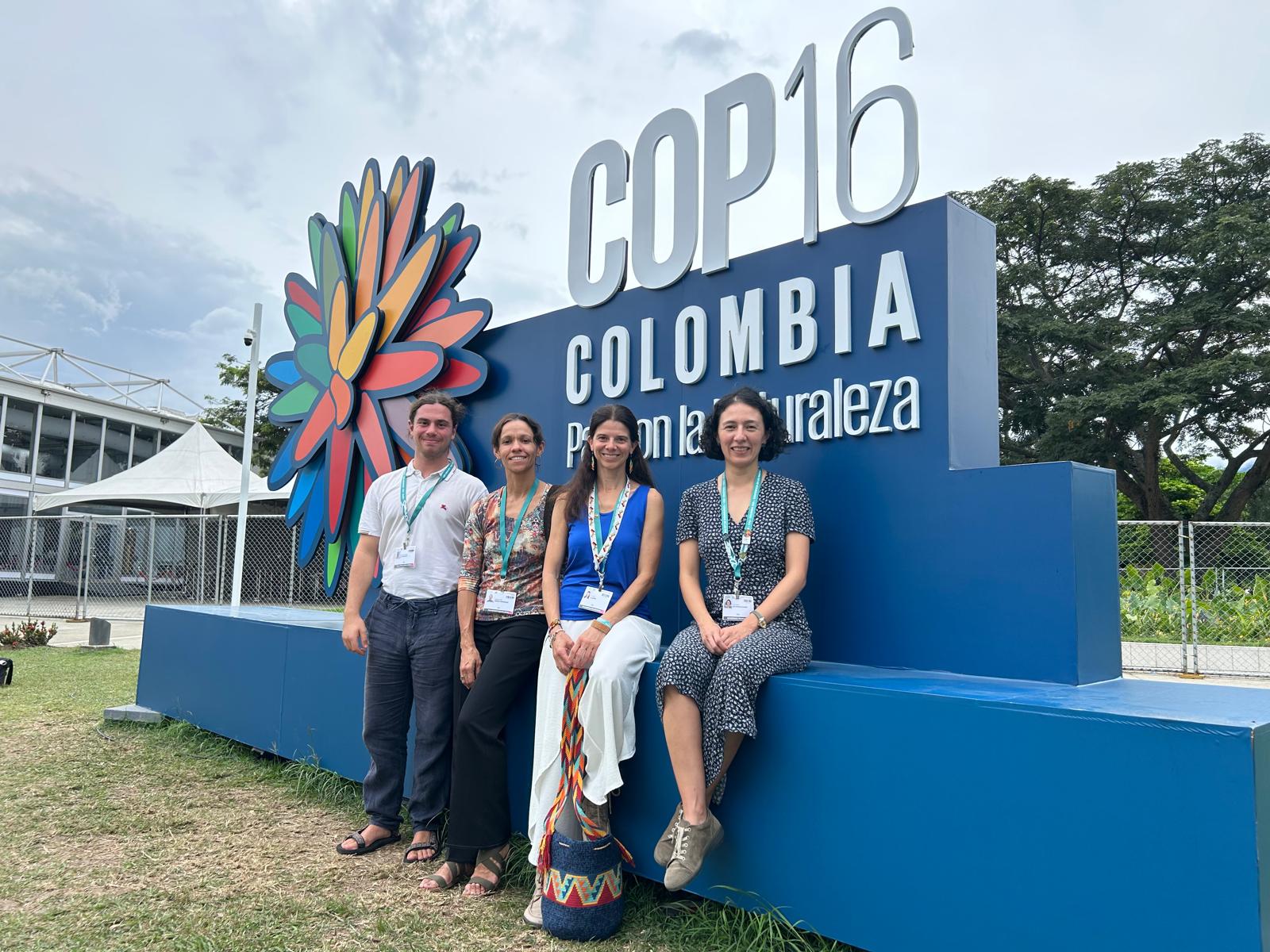

iDiv researchers at the Convention on Biological Diversity’s COP16

Addressing biodiversity challenges with science-based strategies

More19.11.2024 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, TOP NEWS, Unkategorisiert

Soil ecosystem more resilient when land managed extensively

Researchers studied the effects of intensive and extensive land use on soil biodiversity in cropland and grassland

More12.11.2024 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

Diverse and diverging demands on forests in Germany

Research team analyse biodiversity, ecosystems and economics of enriching beech forests with conifers

More

01.11.2024 | Biodiversity and People, TOP NEWS

Aletta Bonn appointed

iDiv researcher has been appointed to the German Advisory Council on Global Change

More21.10.2024 | Biodiversity and People, TOP NEWS

Scientific backing for the join-in campaign ”Unsere Flüsse“ on German television

Researchers investigate the habitat quality of Germany’s streams

More10.10.2024 | Biodiversity and People, TOP NEWS

Julia von Gönner wins Research Award for Citizen Science

The Citizen Science project FLOW mobilised over 900 citizens to contribute to the ecological monitoring of small streams.

More10.10.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, sDiv, TOP NEWS

European forest plants are migrating westwards, nitrogen main cause

Based on a press release by Ghent University

More08.10.2024 | sDiv, TOP NEWS

‘Life on the edge’: A new toolbox to predict global change impact on wildlife

New climate change prediction tool provides insight into population-level vulnerability to global change through combining genomic, geographic and environmental data.

More01.10.2024 | Media Release, Research, Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

Faktencheck Artenvielfalt shows the state of biodiversity in Germany

More than half of Germany’s habitat types have an ecologically unfavourable status

More01.10.2024 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

New Phase for iDiv: Biodiversity Research Consolidated in Central Germany

Today, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) enters a new phase with new funding, a new COO, and a new research group.

More17.09.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

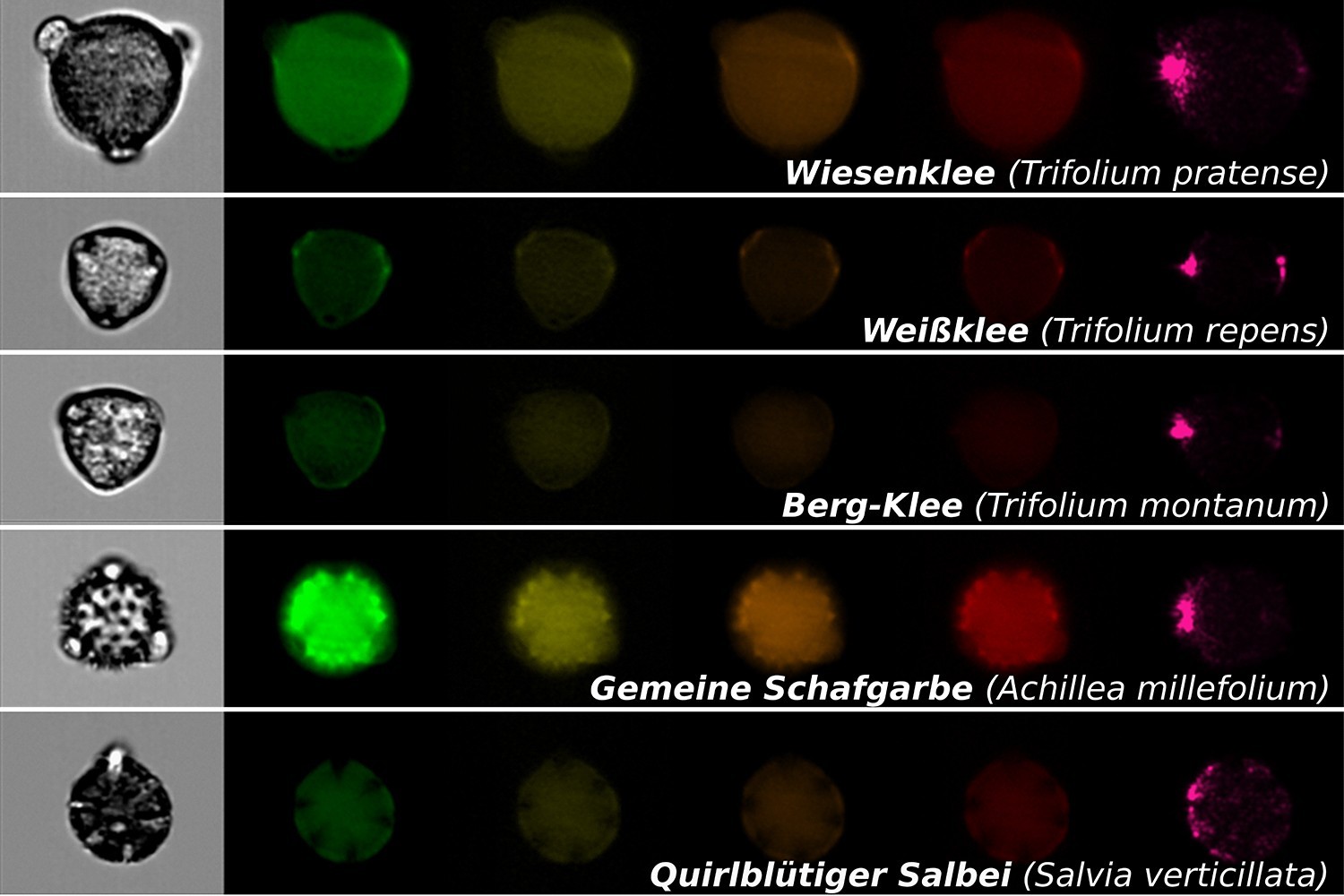

Pollen affects cloud formation and precipitation patterns

New study shows climate impact

More

16.09.2024 | Media Release, MLU News, TOP NEWS

Plants, Ecosystems and Climate Change: International Conference of the German Society for Plant Sciences in Halle

Botanik-Tagung takes place from 15 to 19 September at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg

More10.09.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Cloud cover reduced by large-scale deforestation

Serious impact on climate, say researchers

More09.09.2024 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, MLU News, TOP NEWS

Island life slows animals down

Birds and mammels on islands have a slower metabolism than their closest relatives on the mainland

More06.09.2024 | Biodiversity Economics, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Research Training Group ECO-N has started

Early career researchers study sustainable development

More27.08.2024 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Environmental stressors weaken ecosystem resistance to change

The higher the environmental stress, the lower the resistance to global change.

More21.08.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Healthier honey bees found near organic fields and flower strips

A new study reveals how farming practices affect colony health.

More07.08.2024 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Unlocking the Wealth of Biodiversity Knowledge

Researchers developed a comprehensive framework to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in global biodiversity research

More

22.07.2024 | Media Release, TOP NEWS, UFZ-News

Less productive yet more stable

Low-intensity grassland is better able to withstand the consequences of climate change

More19.07.2024 | Biodiversity and People, Research, TOP NEWS

Considering the mental health implications of nature conservation

Based on a joint text by Imperial College London and the University of Oxford

More09.07.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

How a plant app helps identify the consequences of climate change

Leipzig. A research team led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Leipzig University has developed an algorithm that analyses observational data from the Flora Incognita app. The novel approach described in Methods in Ecology and Evolution can be used to derive ecological patterns that could provide valuable information about the effects of climate change on plants.

More02.07.2024 | Biodiversity and People, Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv, Media Release, Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

What do we need for better biodiversity monitoring in Europe?

Based on a media release of IIASA A new publication in Conservation Letters authored by scientists from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) with a large European consortium provides vital insights into the current status of biodiversity monitoring in Europe, identifying policy needs, challenges, and future pathways.

More28.06.2024 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Research, TOP NEWS

New study helps unravel the paradox of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity

Based on a media release by Professor Dr Jinbao Liao, Yunnan University Habitat fragmentation, a process where a large, continuous habitat is divided into smaller, isolated areas, can both help and harm biodiversity, depending on the total amount of habitat remaining in the landscape, according to a new study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

More26.06.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Closing the Biodiversity Knowledge Gap: Unlocking Biodiversity Insights from the Tropical Andes

Report by Jose Valdez, postdoctoral researcher of Biodiversity Conservation at iDiv and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) Despite hosting some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems and the urgency of the region’s conservation challenges, researchers in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru often struggle to share their unique insights into these complex ecosystems with the global scientific community. This results in a “publication gap” where crucial biodiversity knowledge from the region remains underrepresented in global conversations.

More25.06.2024 | iDiv, Media Release, Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

Germany’s leading role in biodiversity research and policy

More17.06.2024 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, TOP NEWS

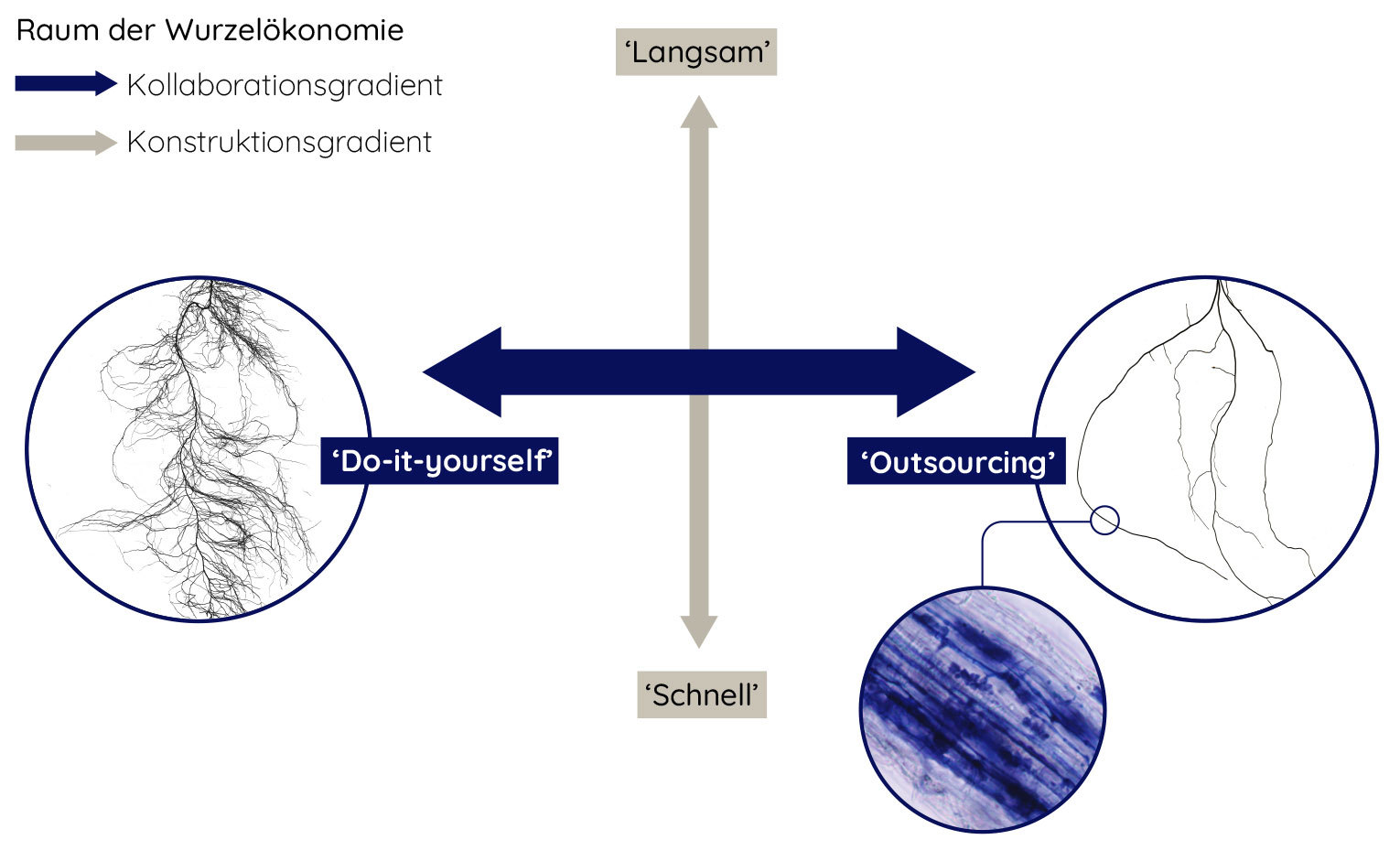

Soil fauna has the potential to fundamentally alter carbon storage in soil

Based on a media release of the Czech Academy of Sciences The life strategies of a multitude of soil faunal taxa can strongly affect the formation of labile and stabilized organic matter in soil, with potential consequences for how soils are managed as carbon sinks, nutrient stores, or providers of food. This is the main conclusion of a review led by a team of researchers from the Czech Academy of Sciences, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University (UL), and the Senckenberg Society for Nature Research. Based on a review of more than 180 scientific articles, the authors highlight major pathways by which soil fauna can influence soil organic matter stability, identify knowledge gaps, and suggest future research directions. The study has recently been published in Nature Communications.

More13.06.2024 | Biodiversity Economics, Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, Physiological Diversity, TOP NEWS

Land management and climate change affect ecosystems’ ability to provide multiple services simultaneously

A novel study published in Nature Communications found that agroecosystems in Central Germany, specifically grasslands and croplands, may have an enhanced capacity to provide multiple goods and services simultaneously when land management reduces the use of pesticides and mineral nitrogen fertiliser.

More30.04.2024 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Low-intensity grazing is locally better for biodiversity but challenging for land users, a new study shows

A team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University (UL), and the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) has investigated the motivation and potential incentives for and challenges of low-intensity grazing among farmers and land users in Europe. The interview results have been published in Land Use Policy.

More26.04.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

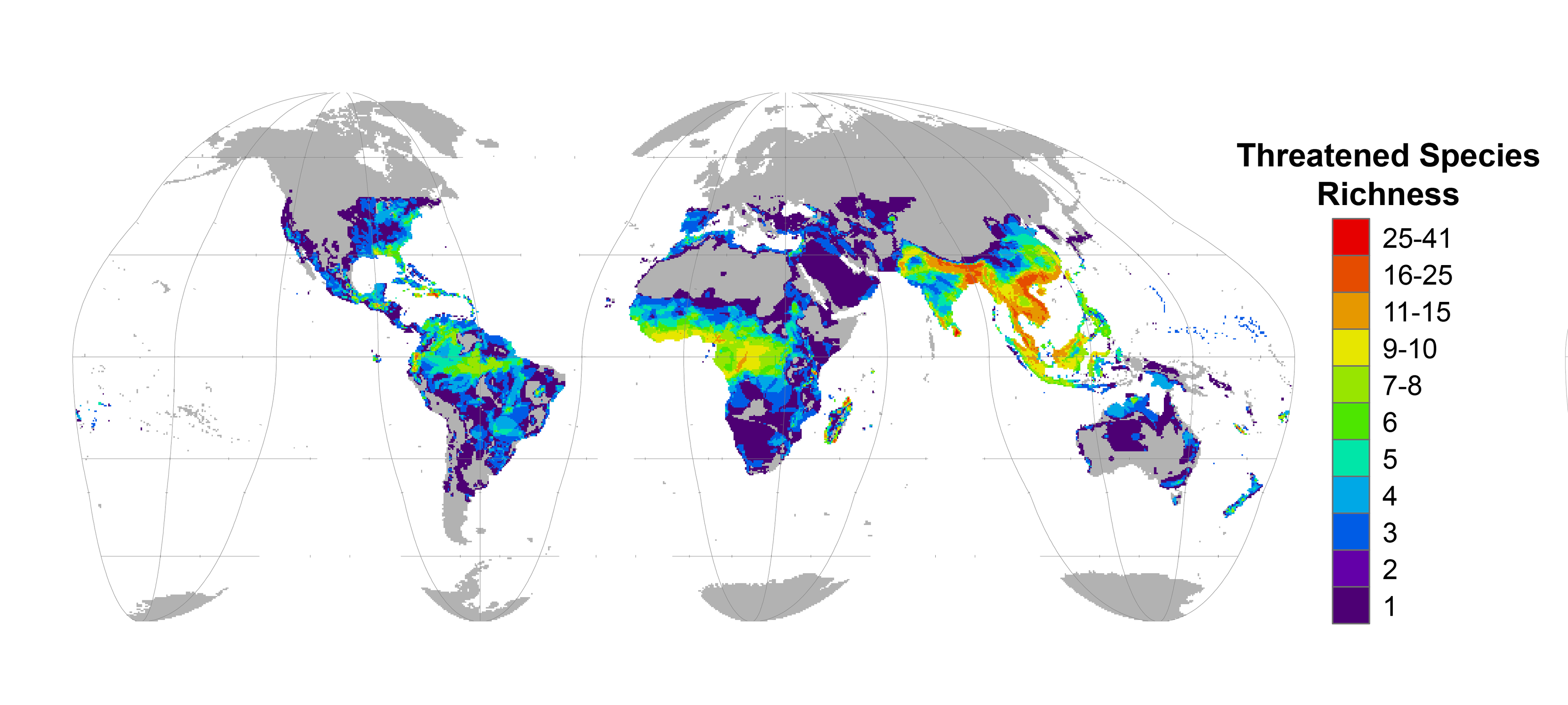

Climate change could become the main driver of biodiversity decline by mid-century

More23.04.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Study shows how plants regulate the climate in Europe

Based on a media release of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg The climate regulates plant growth, but the climate is also regulated by plants. Depending on the vegetation composition, ecosystems even have a strong influence on the climate in Europe, a study by Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) in the journal Global Change Biology shows. The researchers linked satellite data with around 50,000 vegetation records from across Europe. A good five per cent of regional climate regulation can be explained by local plant diversity. The analysis also shows that the effects depend on many other factors. Plants regulate the climate by reflecting sunlight or cooling their surroundings through evaporation.

More18.04.2024 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

iDiv’s Nico Eisenhauer becomes member of the Leopoldina Academy

More17.04.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Rewilding amphibians: Protecting endangered species to restore ecosystems

By Dr Gavin S. Stark, a postdoctoral researcher in the Biodiversity Conservation group at iDiv and lead author of the study.

More12.04.2024 | iDiv Members, TOP NEWS

iDiv’s founding director Christian Wirth Member of the Saxon Academy

More03.04.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Demand for critical minerals puts African great apes at risk

A recent study led by researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the non-profit conservation organization Re:wild shows that the threat of mining to the great ape population in Africa has been greatly underestimated. Their results have been published in Science Advances.

More02.04.2024 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

iDiv is mourning the loss of Diana Wall

Diana Wall passed away on the 25th of March 2024. Diana Wall, a leading environmental scientist and soil ecologist, has been a longstanding member of iDiv’s Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) and part of several research endeavours at iDiv.

More28.03.2024 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

Genetic traces of hierarchy: How social standing shapes the epigenome of Tanzania’s Spotted Hyenas

Based on a media release from the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) A research consortium led by scientists from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig and the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) provide evidence that social behaviour and social status are reflected at the molecular level of gene activation (epigenome) in juvenile and adult free-ranging spotted hyenas. The results, published in the scientific journal Communications Biology, contribute to a better understanding of the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the interplay of social, environmental and physiological factors in the life of a highly social mammal.

More26.03.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, MLU News, TOP NEWS

What do birds and rivers have to do with euro notes?

More14.03.2024 | Media Release, Research, Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

Citizen Science Project FLOW shows that Germany’s small streams are not in a good ecological state

More27.02.2024 | Media Release, Theory in Biodiversity Science, TOP NEWS

Extinctions could result as fish change foraging behaviour in response to rising temperatures

More23.02.2024 | Media Release, sDiv, TOP NEWS

Disentangling Nature’s Contributions to International Trade

Researchers have developed a multi-step process to quantify the dependency of international trade and so-called Nature’s contributions to people. With their new approach, which has been published in People and Nature, the researchers hope to improve knowledge about the complex relationship between nature and international trade.

More22.02.2024 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Research, TOP NEWS

Increasingly similar or different? Centuries-long analysis suggests biodiversity is differentiating and homogenising to a comparable extent

More20.02.2024 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Converting rainforest to plantation impacts food webs and biodiversity

Based on a media release of the University of Goettingen The conversion of rainforest into plantations erodes and restructures food webs and fundamentally changes the way these ecosystems function, according to a new study published in Nature. The findings provide the first insights into the processing of energy across soil and canopy animal communities in mega-biodiverse tropical ecosystems.

More14.02.2024 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Critical Habitats at Risk: Three-quarters of vegetation types in the Americas are under-protected

The study published in Global Ecology and Conservation found that three-quarters of these distinct habitats in North, Central, and South America fall below the Global Biodiversity Convention’s target of 30% protection. The research led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) also highlights that over 40% of threatened bird and mammal species are mostly found in a single vegetation type, putting them at risk for extinction if these critical habitats remain unprotected.

More14.02.2024 | Biodiversity and People, Media Release, TOP NEWS

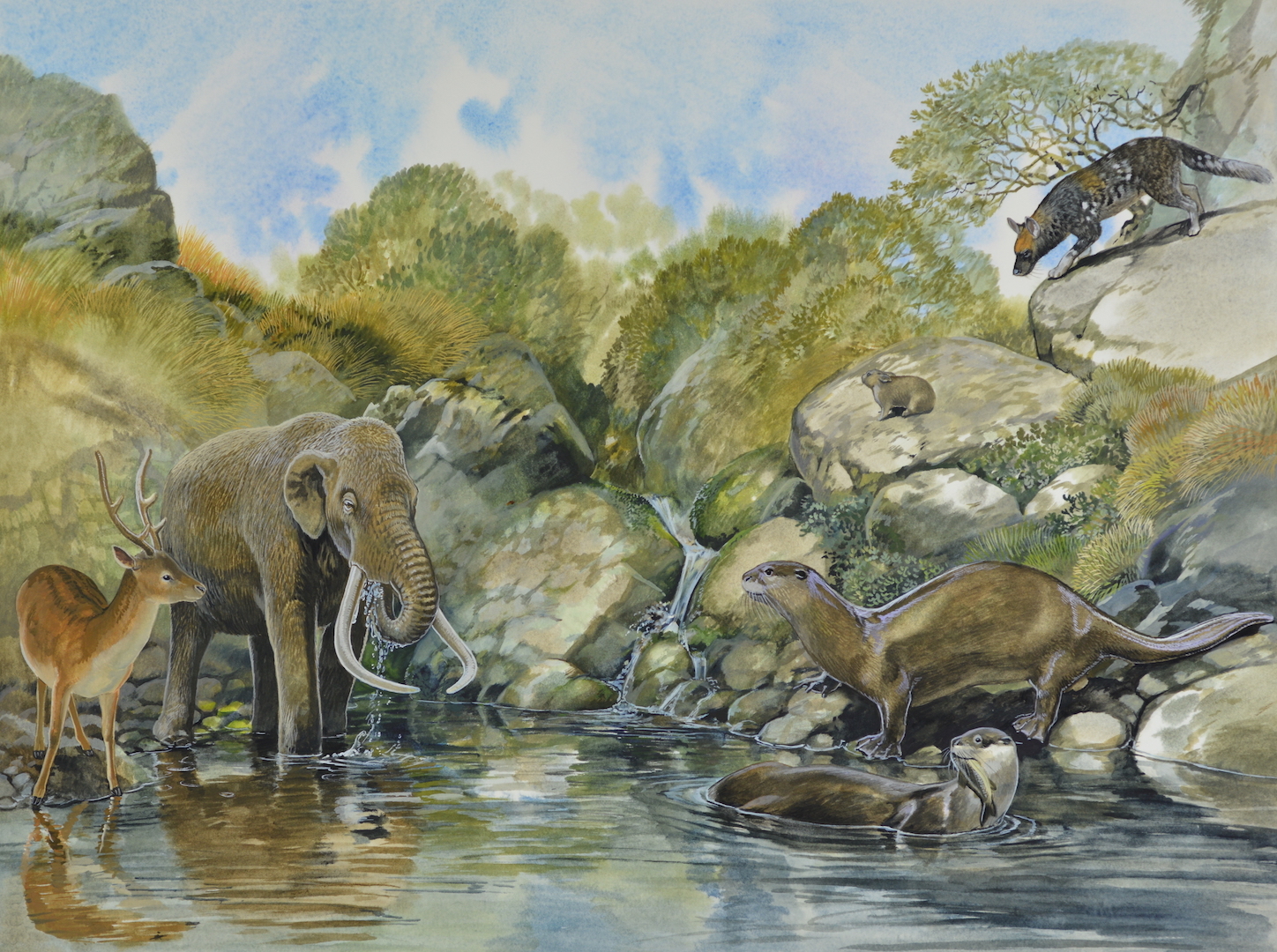

Fish in the upper Danube could be just as endangered in the future as they were in the past, but for different reasons

Based on a media release from the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) Rivers belong to the most threatened ecosystems on Earth. While many studies have projected climate change effects on species, little is known about the severity of these changes compared to historical alterations. Researchers led by the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) explored the vulnerability of 48 native fish species in the upper Danube River Basin to past and potential future environmental changes. They show that fish have been particularly sensitive to changes in flow regimes in the past, while higher temperatures will pose the greatest threat in the future. The threat assessment will remain at least as high in the future. However, it could probably be mitigated by reconnecting former floodplains and improving river connectivity.

More09.02.2024 | Media Release, MLU News, TOP NEWS

Ecologist Brian McGill receives Humboldt Research Award

Based on a media release of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg The Alexander von Humboldt Foundation has honoured US scientist Professor Dr Brian McGill from the University of Maine with the prestigious Humboldt Research Award. The biodiversity researcher was nominated by Professor Dr Jonathan Chase, head of Biodiversity Synthesis at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU). The award is endowed with 60,000 euros. McGill will use the money for several research stays at iDiv.

More22.01.2024 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Wolves and elk are (mostly) welcome back in Poland and Germany’s Oder Delta region, survey shows

An online survey conducted in Germany and Poland shows that large parts of the participants support the return of large carnivores and herbivores, such as wolves and elk, to the Oder Delta region, according to a study published in People and Nature. Presented with different rewilding scenarios, the majority of survey participants showed a preference for land management that leads to the comeback of nature to the most natural state possible. Locals, on the other hand, showed some reservations.

More22.01.2024 | Media Release

Bloom or bust

A new white paper ‘Bloom or bust’, that has been produced by USB together with experts including Dr Miguel Fernandez from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, takes stock of where the world stands on biodiversity loss, existing solutions, and the role that finance, government action, and collaboration can play.

More17.01.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

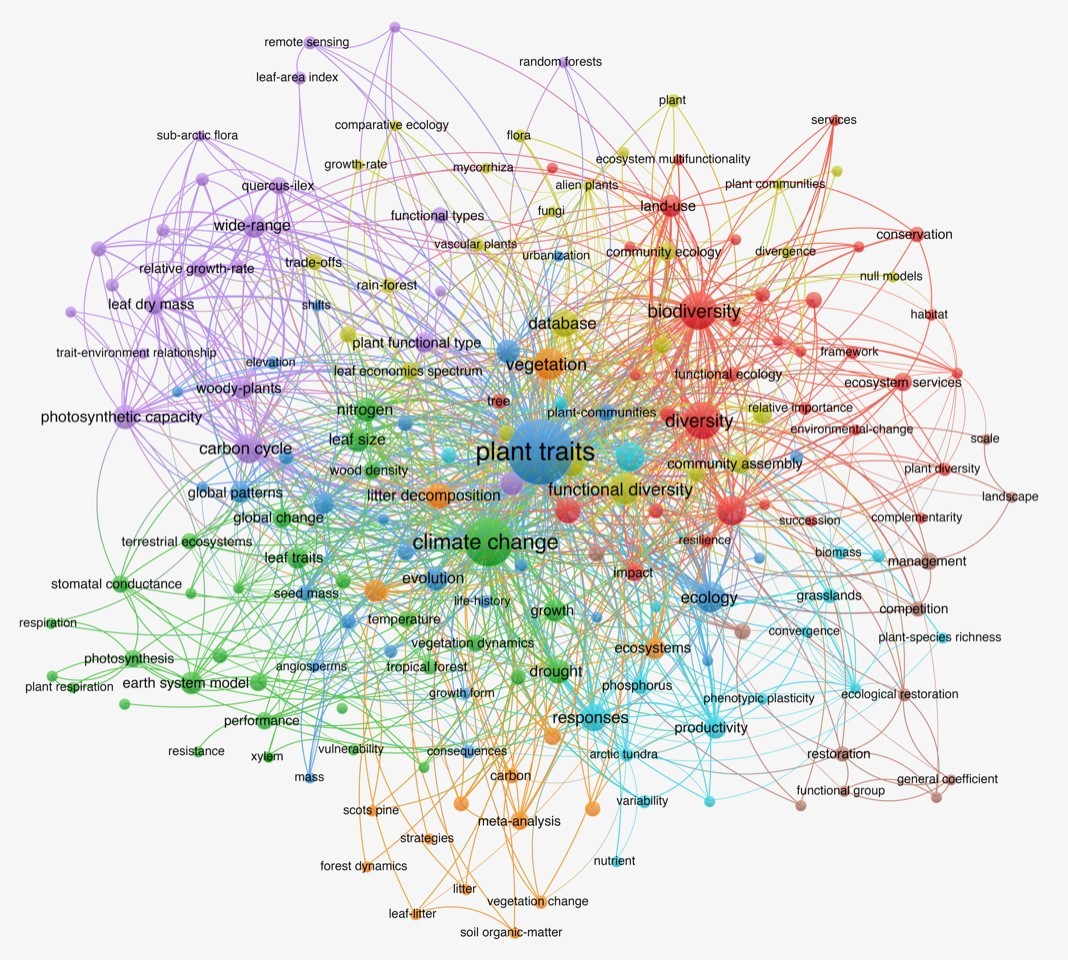

Honoured: Christian Wirth appointed External Member of the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry

Based on a media relase by the Max Planck Institute for BiogeochemistryThe Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry (MPI BGC) has gained a new external member: Prof Dr Christian Wirth has been appointed by the Senate of the Max Planck Society as External Scientific Member at the request of the MPI BGC. Wirth is the founding director and spokesperson of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), professor at Leipzig University and director of the Leipzig Botanical Garden. The plant ecologist investigates the effects of natural and man-made changes in plant biodiversity on ecosystem processes, such as carbon storage, water consumption and energy balance. As a former group leader and later fellow at the MPI BGC, Wirth initiated and supported the development of the TRY database, the world’s largest collection on plant traits. His research on the influence of climate change on biodiversity and ecosystem services of forests ideally complements the research focus of the Max Planck Institute in Jena.

More09.01.2024 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

Global study of extreme drought impacts on grasslands and shrublands

Based on a media release of Colorado State University A global study organized and led by Colorado State University scientists and with participation of several researchers from the German Center for Integraitive Biodiversity Research (iDiv) shows that the effects of extreme drought – which is expected to increase in frequency with climate change – have been greatly underestimated for grasslands and shrublands.

More08.01.2024 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Use of habitat for agricultural purposes puts primate infants at risk

Frequent visits to oil palm plantations are leading to a sharp increase in mortality rates among infant southern pig-tailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) in the wild, according to a new study published in Current Biology. In addition to increased risk from predators and human encounters, exposure to harmful agricultural chemicals in this environment may negatively affect infant development.

More05.01.2024 | Biodiversity Economics, Media Release, Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

Environmental economist: “There is no justification for subsidising agricultural diesel”

More15.12.2023 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

How can Europe restore its nature?

Based on a media release of the University of Duisburg-Essen Early 2024, the European Parliament will take a final vote on the ‘Nature Restoration Law’ (NRL), a globally unique but hotly debated regulation that aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss in Europe. An international team of scientists led by the University of Duisburg-Essen und with contribution from reseachers from the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) as well as the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) investigated the prospects of the new regulation. The article has been published in the Science Magazine.

More15.12.2023 | Biodiversity and People, Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Common insect species are suffering the biggest losses

Leipzig. Insect decline is being driven by losses among the locally more common species, according to a new study published in Nature. Led by researchers at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU), the meta-analysis of 923 locations around the world notes two significant trends: 1) the species with the most individuals (the highest abundance) are disproportionately decreasing in number, and 2) no other species have increased to the high numbers previously seen. This likely explains the frequent observation that there are fewer insects around now than ten, twenty, or thirty years ago.

More13.12.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

How forests smell – a risk for the climate?

Based on a media release of Leipzig University Plants emit odours for a variety of reasons, such as to communicate with each other, to deter herbivores or to respond to changing environmental conditions. An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Leipzig University, the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS) and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) carried out a study to investigate how biodiversity influences the emission of these substances. For the first time, they were able to show that species-rich forests emit less of these gases into the atmosphere than monocultures. In the past, it was assumed that forests with more species would release more emissions. Experiments by the Leipzig team have now disproved this assumption. Their study has been published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

More07.12.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Recommendations for a research agenda on biodiversity and pandemics

Leipzig. An Expert Working Group with involvement of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) has published science-policy recommendations for future research to support transformative pandemic-prevention and preparedness policies. The report was published by Eklipse, a spinoff of a UFZ-led EU project.

More06.12.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Deciphering nature’s climate shield: Plant diversity stabilises soil temperature

Based on a media release of Leipzig University A new study has revealed a natural solution to mitigate the effects of climate change, such as extreme weather events. Researchers from Leipzig University, the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research Halle-Jena-Leipzig (iDiv) and other research institutions have discovered that high plant diversity acts as a buffer against fluctuations in soil temperature. This buffer can then be of vital importance to ecosystem processes. They have just published their new findings in the journal Nature Geoscience.

More04.12.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Ecology: “iDiv Universities” climb to the top of the international Shanghai Ranking 2023

Halle, Jena, Leipzig. The three universities that comprise the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research’s (iDiv) consortium rose to the top of this year’s international Shanghai Ranking in the field of ecology. Of the 5,000 universities evaluated, the universities of Halle, Jena, and Leipzig placed 27th, 51st*, and 35th, respectively. This recognition means Central Germany is home to three of the country’s six highest-ranked universities in the field.

More15.11.2023 | TOP NEWS

Highly Cited Researchers 2023

Clarivate Analytics lists eight iDiv members in its 2023 selection of “Highly Cited Researchers”. According to Clarivate Analytics, these scientists have demonstrated significant influence through the publication of multiple papers, highly cited by their peers, during the last decade.

More13.11.2023 | Biodiversity Economics, iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

DFG gives green light for new Research Training Group

Based on a media release of Leipzig University Another great success for Leipzig in supporting early career researchers: the German Research Foundation (DFG) announced that it will provide around 7 million euros in funding for a new Research Training Group from April 2024. Under the leadership of Professor Martin Quaas, head of Biodiversity Economics at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Leipzig University, more than 40 doctoral researchers in the fields of economics and management science, the natural and life sciences will investigate sustainable concepts for the use of natural common goods.

More13.11.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

When writers write about biodiversity

Based on a media release of Leipzig University Novels and poems often contain descriptions of plants or animals – sometimes more, sometimes less detailed. The extent to which flora and fauna feature in a literary work also depends on who wrote it and under what circumstances. For example, female authors tend to use more species names when they write. This is the conclusion of a research team from Leipzig University, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Goethe University Frankfurt, who examined around 13,500 literary works by approximately 2,900 authors. The study published in People and Nature is an example of how methods from the natural sciences and the humanities can be combined using digital techniques.

More03.11.2023 | Biodiversity Conservation, TOP NEWS

Tailoring Biodiversity Information to Local Needs in the Threatened Tropical Andes

Lima, Halle, Leipzig. Sustainable biodiversity conservation requires cooperation among scientific, societal, economic, and political institutions. In the journal Conservation Science and Practice, researchers have published a new approach to co-designing biodiversity indicators relevant for conservation. They brought together multiple stakeholders in a consultative process, tailoring user-relevant biodiversity information to local needs. The project was led by researchers of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, together with multiple partners in the Tropical Andes. The collaborative approach can serve as a blueprint for making biodiversity information more inclusive, considering the diverse worldviews, values, and knowledge systems between science, policy, and practice.

More30.10.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, Theory in Biodiversity Science, TOP NEWS

Even low levels of artificial light disrupt ecosystems

Leipzig, Jena. A new collection of papers on artificial light at night show the impact of light pollution to be surprisingly far-reaching, with even low levels of artificial light disrupting species communities and entire ecosystems. Published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, the special theme issue, which includes 16 scientific papers, looks at the effects of light pollution in complex ecological systems, including soil, grassland, and insect communities. Led by researchers at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, the collection notes the increasing ubiquity of light pollution, while emphasising the domino effect light pollution has on ecosystem function and stability.

More27.10.2023 | Biodiversity and People, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

How social media can contribute to species conservation

Leipzig. Photos of plant and animal species that are posted on social media can help protect biodiversity, especially in tropical regions. This is the conclusion of a team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (FSU), and the University of Queensland (UQ). Recently published in BioScience, One Earth, and Conservation Biology, the three studies investigated the benefits of using Facebook data for conservation assessments in Bangladesh. The researchers point out that social media can support species monitoring and significantly contribute to conservation assessments in tropical countries.

More10.10.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Funding new research in the Jena Experiment – focus on ecosystem stability

Joint media release from iDiv, Leipzig University and Friedrich Schiller University Jena Jena/Leipzig. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is to fund a Research Unit in the Jena Experiment for a further four years with around five million euros. The scientists, led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University and the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, will focus in particular on the stabilising effect of biodiversity against extreme climate events such as drought, heat and frost.

More09.10.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Mixed forests are more productive when they are structurally complex

Dresden, Halle, Leipzig. Tree species richness increases forest productivity by enhancing aboveground structural complexity. This is the key result of a joint study by TUD Dresden University of Technology, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leuphana University Lüneburg, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Leipzig University, and the University of Montpellier. The results have been published in the journal Science Advances.

More26.09.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Invertebrate decline reduces natural pest control and decomposition of organic matter

Leipzig. The decline in invertebrates also affects the functioning of ecosystems, including two critical ecosystem services: aboveground pest control and belowground decomposition of organic material, according to a new study published in Current Biology and led by researchers at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Leipzig University. The study provides evidence that loss of invertebrates leads to a reduction in important ecosystem services and to the decoupling of ecosystem processes, making immediate protection measures necessary.

More08.09.2023 | Biodiversity Synthesis, iDiv, Research, TOP NEWS

Big fish are shrinking and small fish are multiplying, a new study shows

Based on a media release from the University of St. Andrews St. Andrews/Leipzig. Organisms are becoming smaller through a combination of species replacement, and changes within species. Published in Science, the research looked at time series covering the past 60 years, from many types of animals and plants around the world. The study was conducted by an international team of scientists from 17 universities, as part of a working group funded by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), and led by scientists of the University of St Andrews, and the University of Nottingham.

More08.09.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

iDiv’s early career researchers’ response to the proposed changes to the WissZeitVG

iDiv’s researchers1 are concerned about the already precarious working conditions in German academia and are alarmed that the proposed changes to the WissZeitVG will exacerbate this.

More04.09.2023 | Biodiversity Conservation, Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Most species are rare. But not very rare

Halle/Saale, Fort Lauderdale. More than 100 years of observations in nature have revealed a universal pattern of species abundances: Most species are rare but not very rare, and only a few species are very common. These so-called global species abundance distributions have become fully unveiled for some well-monitored species groups, such as birds. For other species groups, such as insects, however, the veil remains partially unlifted. These are the findings of an international team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the University of Florida (UF), published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution. The study demonstrates how important biodiversity monitoring is for detecting species abundances on planet Earth and for understanding how they change.

More01.09.2023 | iDiv, TOP NEWS

New map on potentially groundwater-dependent vegetation in the Mediterranean biome

Report by Léonard El-Hokayem, doctoral student at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle. Decreasing rainfall and increased groundwater use are threatening vegetation and ultimately biodiversity in the Mediterranean biome. Plants that depend on groundwater are particularly vulnerable. We have developed a novel, easy-to-use index to map potentially groundwater dependent vegetation (pGDV) based on environmental site conditions and vegetation characteristics. Our concept combines globally-available geodata and remote sensing and has recently been published in Science of The Total Environment. The results indicate that 31 % of the natural vegetation in the Mediterranean likely depends on groundwater. A biome-wise map of pGDV is important to prioritise areas for detailed identification of actual GDV and biodiversity conservation.

More25.08.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

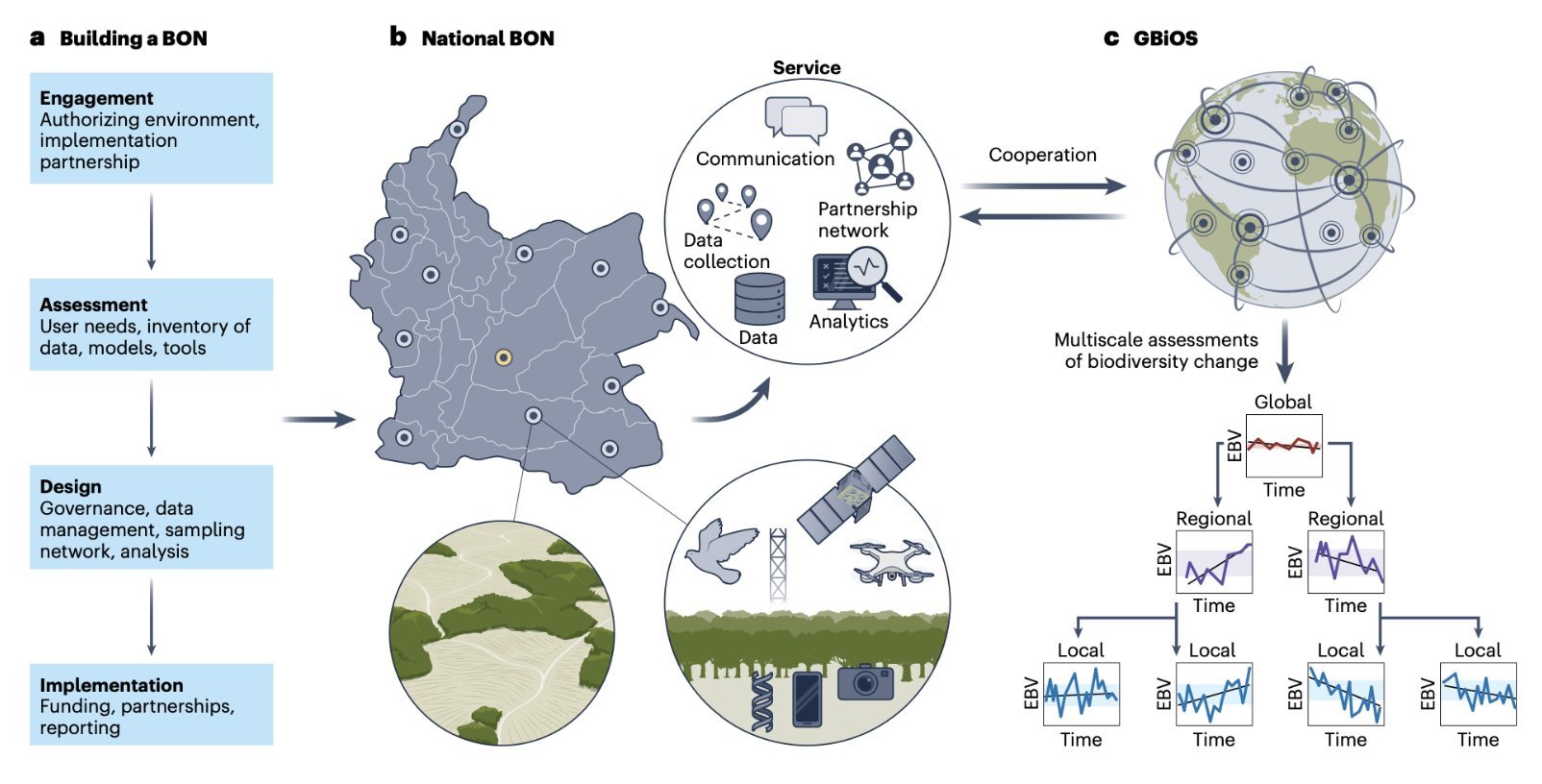

A global observatory to monitor Earth’s biodiversity

Based on a media release of GEO BON The Global Biodiversity Observing System (GBiOS) is a proposal developed by scientists from the Group on Earth Observations Biodiversity Observation Network (GEO BON), and its partners, including the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv). It will combine technology, data, and knowledge from around the world to foster collaboration and data sharing among countries and to provide the data urgently needed to monitor biodiversity change and target action. The proposal for this novel system was published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

More23.08.2023 | iDiv, iDiv Members, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

1000 new species for Nigeria

Leipzig/Katsina. To date, over 1000 vascular plants in Nigeria may be undescribed, making it impossible to know whether or not these plants are endangered and in need of protection. This is one of the key results of a new study led by researchers from the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Leipzig University, published in Annals of Botany. In order to meet the targets of the CBD’s Global Biodiversity Framework, urgent measures are required that promote local taxonomic activities.

More15.08.2023 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

Some plants do not shed their leaves in autumn, for good reason

Report by Dr Gerrit Angst, postdoctoral researcher of the Experimental Interaction Ecology at iDiv, Leipzig University, and the Czech Academy of Sciences and co-author: Leipzig/Budweis/Prague. Retention of dead biomass by plants is common in the temperate herbaceous flora and can be related to certain plant traits, indicating relevance to ecosystem functioning. These are the main findings of an experimental study on more than 100 plant species jointly performed by researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University, the Czech Academy of Sciences, and the Charles University, Prague. The study has recently been published in the Journal of Ecology.

More08.08.2023 | Media Release, sDiv, TOP NEWS

Satellite documentation of effects of heat waves on plants

More12.07.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Remote plant worlds

Based on a media release by the University of Göttingen Oceanic islands provide useful models for ecology, biogeography and evolutionary research. Many ground-breaking findings – including Darwin’s theory of evolution – have emerged from the study of species on islands and their interplay with their living and non-living environment. Now, an international research team led by researchers from the University of Göttingen and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) has investigated the flora of the Canary Island of Tenerife. The results were surprising: the island’s plant-life exhibits a remarkable diversity of forms. However, the plants differ little from mainland plants in functional terms. However, unlike the flora of the mainland, the flora of Tenerife is dominated by slow-growing, woody shrubs with a “low-risk” life strategy. The results were published in Nature.

More15.06.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Holistic management is key to increase carbon sequestration in soils

Report by Dr Gerrit Angst, postdoctoral researcher of the Experimental Interaction Ecology at iDiv, Leipzig University, and the Czech Academy of Sciences and first author: Leipzig/Budweis/Copenhagen. Increased carbon sequestration in soil to help mitigate climate change can only be achieved by a more holistic management. This is the conclusion from our opinion paper conceptualized together with colleagues from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University, the Czech Academy of Sciences, and the University of Copenhagen. We developed a novel framework that can guide informed and effective management of soils as carbon sinks. The study has recently been published in Nature Communications.

More26.04.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, Theory in Biodiversity Science, TOP NEWS

Diverse landscapes help insects cope with heat stress

Leipzig/Jena/Bad Lauchstädt. Global warming is affecting terrestrial insects in multiple ways. In response to increasingly frequent heat extremes, they have to either reduce their activity or seek shelter in more suitable microhabitats. A new study led by researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Friedrich Schiller University Jena shows: The more diverse these microhabitats are, the better for the insects. For their study, published in Global Change Biology, they developed a new approach to accurately track insect movements and activity.

More20.04.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

iDiv celebrates its 10th anniversary

The German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) celebrated its 10th anniversary today with a ceremony in the Leipzig University Paulinum. Over 300 guests from politics, science and civil society took part, including the ministers-president of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia, Michael Kretschmer, Dr Reiner Haseloff and Bodo Ramelow as well as the Federal Government Commissioner for eastern Germany, Carsten Schneider. They acknowledged the research centre’s important contributions to the protection of biological diversity. In his welcoming message, Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz stressed the importance of “world-class basic research” for international biodiversity policy.

More19.04.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, Research, Theory in Biodiversity Science, TOP NEWS

Large animals travel more slowly because they can’t keep cool

Leipzig. Whether an animal is flying, running or swimming, its traveling speed is limited by how effectively it sheds the excess heat generated by its muscles, according to a new study led by Alexander Dyer from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, published in the open access journal PLOS Biology.

More30.03.2023 | Biodiversity Synthesis, iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

New ideas for biodiversity research: ecologist Jonathan Chase receives ERC Advanced Grant

Joint media release of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg The European Research Council (ERC) announced that Prof. Dr. Jonathan Chase will be awarded one of the prestigious ERC Advanced Grants. The scientist will receive almost 2.5 million euros over the next five years to fund his research project “MetaChange”. With this project, he plans to develop new concepts, tools and analyses for a better understanding of biodiversity and its change. Chase has been conducting research and teaching at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) since 2014.

More20.03.2023 | Biodiversity Synthesis, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Widespread species gaining ground

Leipzig/Halle. Human activities are accelerating biodiversity change and promoting a rapid turnover in species composition. A team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) has now shown that more widespread species tend to benefit from anthropogenic changes and increase the number of sites they occupy, whereas more narrowly distributed species decrease. Their results, which were published in Nature Communications, are based on an extensive dataset of over 200 studies and provide evidence that habitat protection can mitigate some effects of biodiversity change and reduce the systematic decrease of small-ranged species.

More16.03.2023 | Biodiversity Economics, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

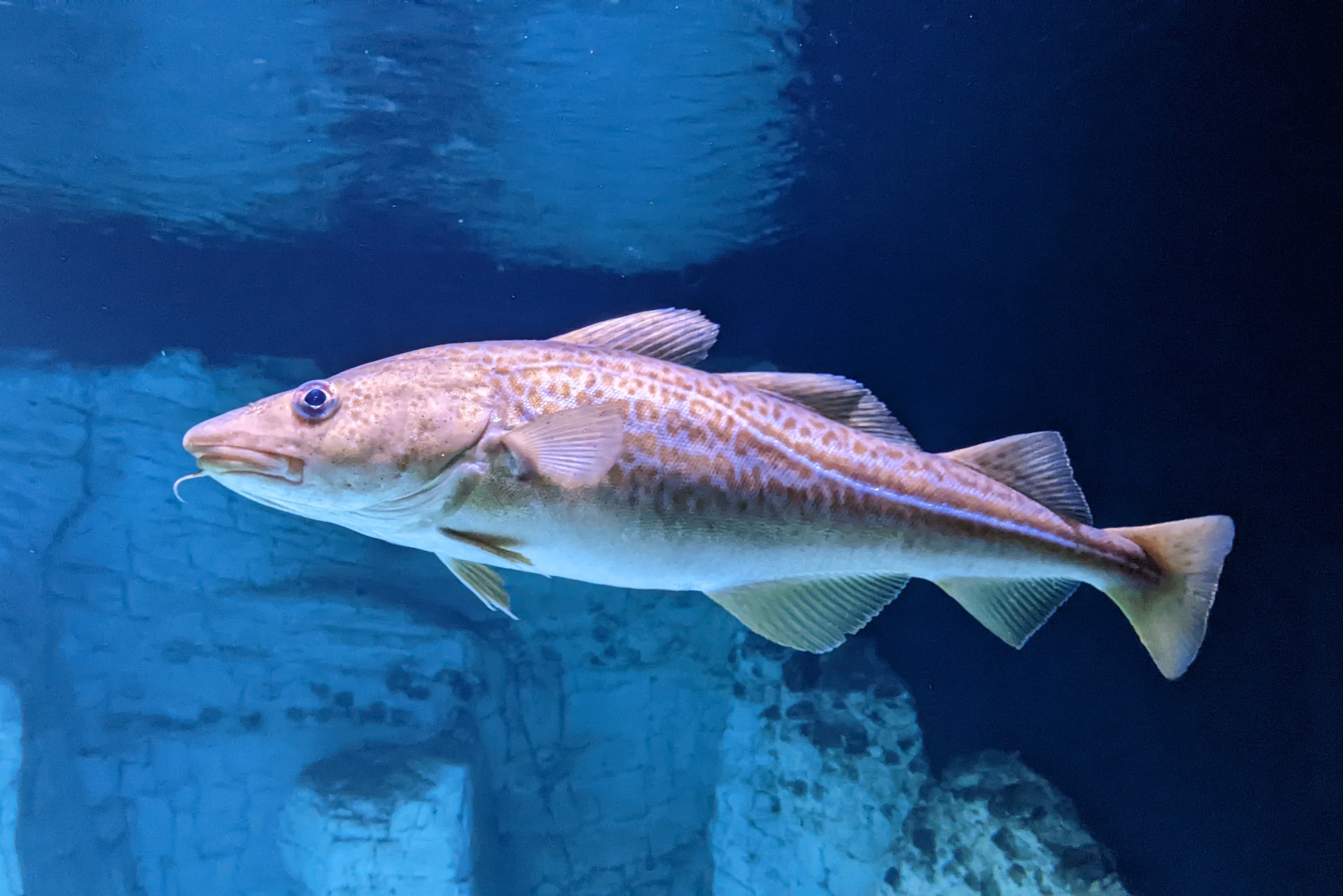

How fishermen benefit from reversing evolution of cod

Leipzig. Intense fishing and overexploitation have led to evolutionary changes in fish stocks like cod, reducing both their productivity and value on the market. These changes can be reversed by more sustainable and far-sighted fisheries management. The new study by researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University and the Institute of Marine Research in Tromsø, which was published in Nature Sustainability, shows that reversal of evolutionary change would only slightly reduce the profit of fishing, but would help regain and conserve natural genetic diversity.

More09.03.2023 | Biodiversity Synthesis, iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Dwarfs and giants on islands more likely to go extinct

Leipzig/Halle. Islands are “laboratories of evolution” and home to animal species with many unique features, including dwarfs that evolved to very small sizes compared to their mainland relatives, and giants that evolved to large sizes. A team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) has now found that species that evolved to more extreme body sizes compared to their mainland relatives have a higher risk of extinction than those that evolved to less extreme sizes. Their study, which was published in Science, also shows that extinction rates of mammals on islands worldwide increased significantly after the arrival of modern humans.

More09.03.2023 | iDiv Members, Media Release, MLU News, Research, TOP NEWS

Global climate data insufficiently explain composition of local plant species

Based on a media release of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg The global climate influences regional plant growth – but not to the same extent in all habitats. This finding was made by geobotanists at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and members of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) after analysing over 300,000 European vegetation plots. Their conclusion: No general prediction can be made about the effects of climate change on the Earth’s vegetation; instead, the effects depend to a large degree on local conditions and the habitat under investigation. The findings were published in the renowned journal Nature Communications.

More07.03.2023 | Media Release, TOP NEWS

Plant roots fuel tropical soil animal communities

Based on a media release by the University of Göttingen Göttingen/Leipzig. Soil animal communities in the tropics are driven by plant roots and the resources derived from them. This is the main finding of a new study of a research team led by the University of Göttingen, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Leipzig University. Millions of small creatures toiling in a single hectare of soil including earthworms, springtails, mites, insects, and other arthropods are crucial for decomposition and soil health. For a long time, it has been believed that leaf litter is the primary resource for these animals. However, this recent study published in the journal Ecology Letters shows that litter doesn’t play any crucial role at all for the tropical soil fauna.

More01.03.2023 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

European conservation leaders gather to boost collective dialogue for a Trans-European Nature Network

Based on a media release by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) Brussels, 28 February 2023. More than 70 leading EU policy and governmental decision-makers joined to lay the foundation for a bold new vision for Europe’s nature protection in the first NaturaConnect Stakeholder Event this year. Organised by the Horizon Europe NaturaConnect project, the event welcomed a diverse range of influential stakeholders, from country representatives to European Union delegates and international and European conservation organisations. At the heart of the NaturaConnect project is the goal of supporting the creation of a Trans-European Nature Network (TEN-N) of protected and connected areas that conserve at least 30% of land in the EU and benefit both nature and people. The new project is conducted by international partners from research and environmental organisations, led by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU).

More10.02.2023 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

How does biodiversity change globally? Detecting accurate trends may be currently unfeasible

Leipzig/Halle. Existing data are too biased to provide a reliable picture of the global average of local species richness trends. This is the conclusion of an international research team led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU). The authors recommend prioritising local and regional assessments of biodiversity change instead of attempting to quantify global change and advocate standardised monitoring programmes, supported by models that take measurement errors and spatial biases into account. The study was published in the journal Ecography.

More09.02.2023 | Media Release, Molecular Interaction Ecology, Physiological Diversity, TOP NEWS

How could we evolve such a huge brain?

Based on a media release by the University of Amsterdam Amsterdam/Leipzig/Jena. A new study, published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, investigated the foraging behaviour of children in a present-day forager society. Already from an early age, there was a gender-specific development of foraging skills. These new findings, combined with the high level of food sharing in forager societies, support the embodied capital theory, offering an explanation for the substantially larger brains in humans. Foraging skills could have provided humans with a more stable energy and nutrient supply, which may ultimately have enabled large resource investments into the brain. The research was led by the University of Amsterdam (UvA), the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), and the Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

More07.02.2023 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, Physiological Diversity, TOP NEWS

Plant diversity may never fully recover from agriculture without a helping hand

Leipzig/Minnesota. Agriculture is considered a major disturbance for ecological systems – the recovery of degraded or formally used agricultural land might take a long time. However, without any active restoration interventions, this recovery can take an exceedingly long time and is often incomplete, as shown by a team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University (UL), Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ). Their study, which was published in the Journal of Ecology, sheds light on the recovery process at different scales in former agricultural sites, pointing to specific restoration interventions that could help biodiversity to recovery.

More01.02.2023 | Biodiversity and People, Media Release, TOP NEWS

76 per cent of assessed insect species not adequately covered by protected areas

Leipzig/Jena. Insect numbers have been declining over the past decades in many parts of the world. Protected areas could safeguard threatened insects, but a team of researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), the Friedrich Schiller University Jena and the University of Queensland now found that 76 per cent of globally assessed insect species are not adequately covered by protected areas worldwide. In the journal One Earth, the researchers encourage decision-makers to give more consideration to the by far biggest species group in implementing the new goals of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

More17.01.2023 | iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Implementing global biodiversity targets in Germany – with support from research

Berlin. Implementation of the recently agreed UN nature conservation targets will only succeed if all stakeholders – from policy and practice, civil society, business and science – work together. Science provides the knowledge base for effective action, thus playing a key role in the implementation of these global objectives. This was the tenor of discussion at the parliamentary evening on 17 January in the State Representation of Saxony-Anhalt in Berlin, to which the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Saxony-Anhalt Ministry of Science, Energy, Climate Protection and the Environment had invited. The scientists call for a high-level national biodiversity council as an essential element in making the conservation of biological diversity a core political issue across all relevant ministries.

More13.01.2023 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Grassland ecosystems become more resilient with age

Based on a media release of the University of Zurich Zurich/Leipzig. Recent experiments have shown that the loss of species from a plant community can reduce ecosystem functions and services such as productivity, carbon storage and soil health. With the loss of functioning the ecosystem may also become destabilized in its ability to maintain ecosystem functions and services in the long-term. However, assessing this is only possible if experiments can be maintained for a sufficient length of time.

More03.01.2023 | Media Release, Species Interaction Ecology, TOP NEWS, UFZ-News

Fewer moths, more flies

In the far north of the planet, climate change is clearly noticeable. A new study in Finland now shows that in parallel there have been dramatic changes in pollinating insects. Researchers from the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU), the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research Halle-Jena-Leipzig (iDiv) have discovered that the network of plants and their pollinators there has changed considerably since the end of the 19th century. As the scientists warn in an article published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, this could lead to plants being pollinated less effectively. This, in turn, would adversely affect their reproduction.

More02.01.2023 | Biodiversity Conservation, TOP NEWS

wildE: Restoring wild habitats in Europe against climate change

Based on a media release by INRAE Cestas/Halle. Terrestrial ecosystems throughout Europe face the twin threats of climate change and the loss of biodiversity. “Rewilding” could be an important ecological restoration solution to mitigate both of these issues, but up to now, it is mostly restricted to local initiatives scattered across the continent focussing on biodiversity objectives alone. The wildE project aims to assess the synergies between climate change mitigation, adaptation and biodiversity and thus to improve the potential of climate-smart rewilding as a nature-based solution for ecological restoration in Europe. wildE is funded by the EU Horizon programme and coordinated by the French National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment INRAE with the participation of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

More15.12.2022 | iDiv Members, TOP NEWS

Identification of groundwater-dependent vegetation via satellites

Report by Léonard El-Hokayem (doctoral researcher at MLU and iDiv) Halle. Groundwater in (semi)-arid regions plays a key role in sustaining important terrestrial ecosystems, providing drinking water and supporting agriculture. We developed a new multi-instrument framework to identify groundwater-dependent vegetation (GDV) in these regions. Therefore, a combination of satellite images and other environmental data got tested and validated in a Mediterranean study area in Southern Italy. The developed concept was recently published in Ecological Indicators. It allows for the identification and study of vegetation that relies on groundwater, and thus can help protect these biodiversity hotspots and the ecosystem services they provide.

More14.12.2022 | Macroecology and Society, Media Release, sDiv, TOP NEWS

Humans and nature: The distance is growing

Joint media release by iDiv and Leipzig University Leipzig/Moulis. Humans are living further and further away from nature, leading to a decline in the number of our interactions with nature. This is the finding of a meta-study conducted by a Franco-German research team at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Leipzig University and the Theoretical and Experimental Ecology Station (SETE – CNRS). The researchers highlight that human experience of nature is crucial for developing pro-environmental behaviour and thus facing the global environmental crisis. The study has been published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

More12.12.2022 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv, Media Release, TOP NEWS

A novel and efficient method for monitoring Asian otters

South-east Asia is a melting pot of otters that are very difficult to monitor in the wild. We developed and tested a novel, accurate, and affordable DNA-based method to reliably identify three endemic Asian otter species in a paper published today in Ecology and Evolution. The protocol developed by our team of South Asian researchers from the Malaysian Nature Society, Sunway University, Department of Wildlife and National Parks (PERHILITAN), Peninsular Malaysia, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) will help in monitoring and conservation of threatened otter species in Asia. We also highlight the importance and need of cost-effective and replicable techniques to advance biodiversity monitoring in highly biodiverse yet under-represented parts of the world.

More08.12.2022 | Biodiversity and People, iDiv, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS, UFZ-News

Valid Data from Citizen Science

More01.12.2022 | TOP NEWS

Award for Prof. Walter Rosenthal

Jena. The President of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Prof. Walter Rosenthal, has been named “University Manager of the Year 2022”. Rosenthal has been Chair of the iDiv Board of Trustees since 2018.

More30.11.2022 | iDiv, iDiv Members, TOP NEWS

Biodiversity under climate extremes: Patient and Healer

Leipzig. The world is experiencing two megatrends: Climate extremes are increasing in magnitude and frequency while biodiversity is declining. Writing in Nature, researchers from Leipzig University and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) with collaborators across Europe, express concern that these two trends can mutually exacerbate each other. The researchers call for a new research agenda emphasizing the interconnecting risks of climate extremes and biodiversity decline.

More27.11.2022 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

New Senckenberg Institute to be established in Jena

More24.11.2022 | iDiv, Research, TOP NEWS

Increased grazing pressure threatens the most arid rangelands

Based on a media release of the University of Alicante Grazing can have positive effects on ecosystem services, particularly in species-rich rangelands. However, these effects turn to negative under a warmer climate. This was found by a team of researchers led by the University of Alicante (UA) and with participation of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv). The study, which was published in Science, reports results from the first-ever global field assessment of the ecological impacts of grazing in drylands.

More15.11.2022 | TOP NEWS

Highly Cited Researchers 2022

Clarivate Analytics lists seven iDiv members in its 2022 selection of “Highly Cited Researchers”. According to Clarivate Analytics, these scientists have demonstrated significant influence through the publication of multiple papers, highly cited by their peers, during the last decade.

More10.11.2022 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

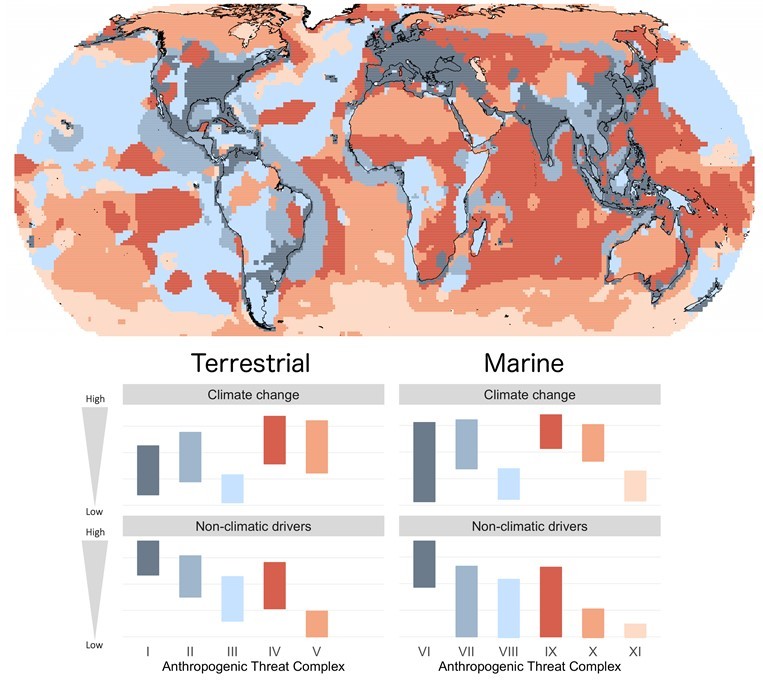

Deforestation and grassland conversion are the biggest causes of biodiversity loss

Based on a media release by Natural History Museum London Luxembourg/London/Halle. The conversion of natural forests and grasslands to agriculture and livestock is the biggest cause of global biodiversity loss. The next biggest drivers are the exploitation of wildlife through fishing, logging, trade and hunting – and then pollution. Climate change ranks fourth on land so far but second in oceans. This is the main result of an international study led by researchers from Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC) in Argentina, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Natural History Museum London. The study, published in Science Advances, demonstrates that fighting climate change alone will not be enough to prevent the further loss of biodiversity.

More10.11.2022 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Protecting and connecting nature across Europe

Based on a media release by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) Vienna/Leipzig. Europe needs healthy ecosystems that benefit biodiversity and people and are resilient to climate change. The Horizon Europe NaturaConnect Project will support European Union governments and other public and private institutions in designing a coherent, resilient and well-connect Trans-European Nature Network. The new project is conducted by international partners from research and environmental organisations, led by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin-Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU).

More24.10.2022 | Biodiversity Synthesis, Media Release, Physiological Diversity, TOP NEWS

More yield, fewer species: How human nutrient inputs alter grasslands

Leipzig. With high nutrient inputs in grasslands, more plant species get lost over longer periods of time than new ones can establish. In addition, fewer new species settle than under natural nutrient availability. With a worldwide experiment, researchers led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) have now been able to show why additional nutrient inputs reduce plant diversity in grasslands. Another finding was that the increase in biomass with nutrient inputs is due to a few plant species that can use higher nutrient inputs to their advantage and remain successfully at a site over long periods of time. The results have been published in the journal Ecology Letters.

More20.10.2022 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Smartphone data can help create global vegetation maps

Leipzig. Missing knowledge in the global distribution of plant traits could be filled with data from species identification apps. Researchers from Leipzig University, the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and other institutions were able to demonstrate this based on data from the popular iNaturalist app. Supplemented with data on plant traits, iNaturalist input results in considerably more precise maps than previous approaches based on extrapolation from limited databases. Among other things, the new maps provide an improved basis for understanding plant-environment interactions and for Earth system modelling. The study has been published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

More19.10.2022 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Ecological imbalance: How plant diversity in Germany has changed in the past century

Based on a media release by Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) Halle. Germany’s plant world has seen a greater number of losers than winners over the past one hundred years. While the frequencies and abundances of many species have shrunk, they have significantly increased in others. This has resulted in a very uneven distribution of gains and losses. It indicates an overall, large-scale loss of biodiversity, as a team led by the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) reports in Nature.

More17.10.2022 | iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

European colonial legacy is still visible in today’s alien floras

Based on a media release by the University of Vienna Vienna/Leipzig. Alien floras in regions that were once occupied by the same European power are, on average, more similar to each other compared to outside regions and this similarity increases with the length of time a region was occupied. This is the conclusion of a study by an international team of researchers led by the University of Vienna and with the participation of researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv). The results were recently published in the scientific journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

More12.10.2022 | Experimental Interaction Ecology, Media Release, TOP NEWS

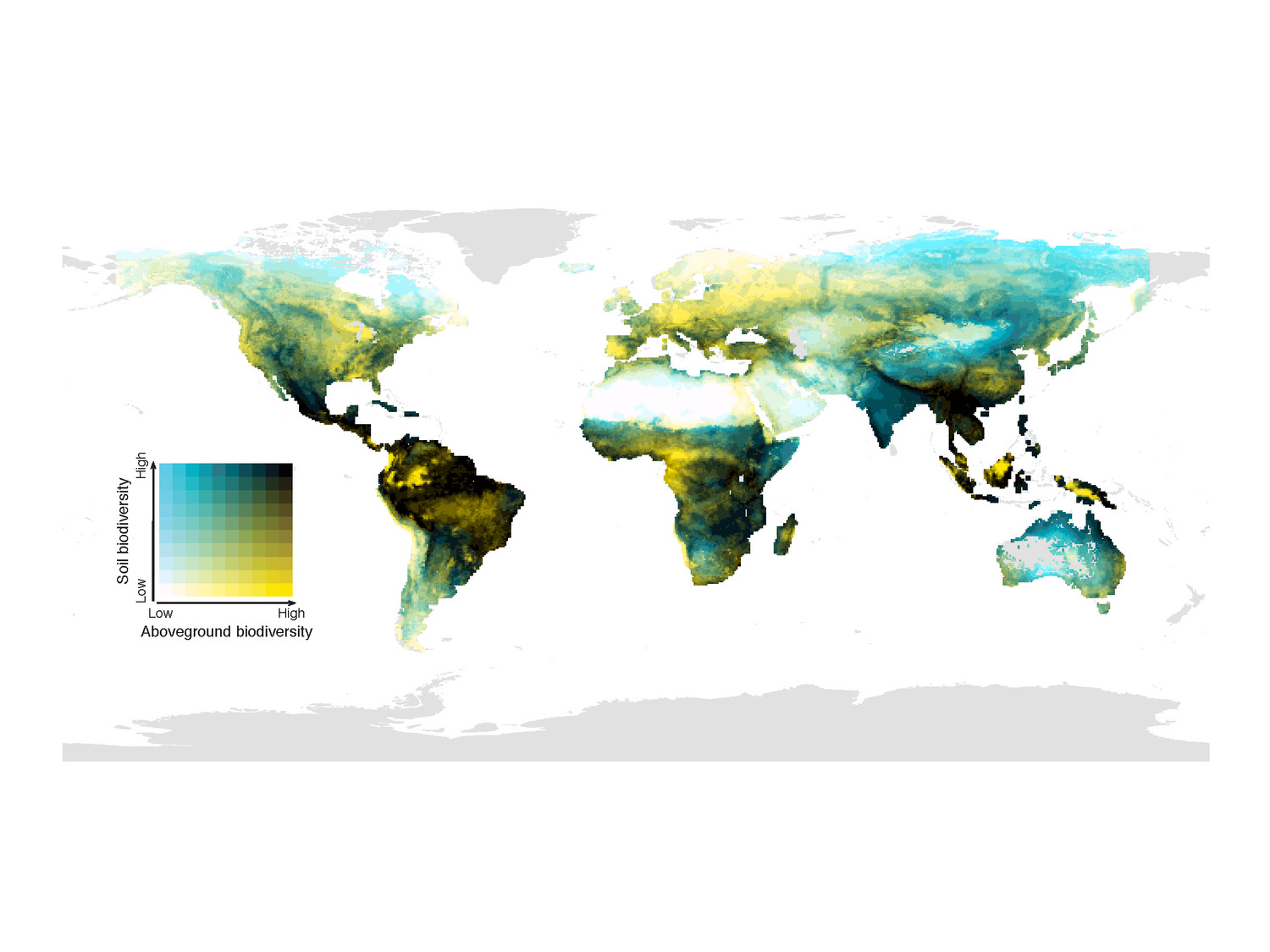

Global study: Few of the ecologically most valuable soils are protected

Halle, Leipzig, Seville. Current protected areas only poorly cover the places most relevant for conserving soil ecological values. This is the conclusion of a new study published in the journal Nature. To assess global hotspots for preserving soil ecological values, an international team of scientists measured different dimensions of soil biodiversity (local species richness and uniqueness) and ecosystem services (like water regulation or carbon storage). They found that these dimensions peaked in contrasting regions of the world. For instance, temperate ecosystems showed higher local soil biodiversity (species richness), while colder ecosystems were identified as hotspots of soil ecosystem services. In addition, the results suggest that tropical and arid ecosystems hold the most unique communities of soil organisms. Soil ecological values are often overlooked in nature conservation management and policy decisions; the new study, published in Nature, demonstrates where efforts to protect them are needed most.

More01.10.2022 | Macroecology and Society, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Land tenure drives deforestation rates in Brazil

Leipzig. Tropical deforestation causes widespread degradation of biodiversity and carbon stocks. Researchers from the German Center of Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Leipzig University were now able to test the relationship between land tenure and deforestation rates in Brazil. Their research, which was published in Nature Communications, shows that poorly defined land rights go hand in hand with increased deforestation rates. Privatising these lands, as is often promoted in the tropics, can only mitigate this effect if combined with strict environmental policies.

More29.09.2022 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

Historical reduction of the wolf in the Iberian Peninsula

Based on a media release of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Spain (CSIC) Seville/Leipzig. The distribution of the wolf covered at least 65% of the Iberian Peninsula in the mid-19th century. Compared to this finding, recent expansions mean little more than a stabilisation of the species. This is the result of a study led by the Doñana Biological Station of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (EBD-CSIC) in collaboration with the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU). To reach these conclusions, the research team analysed the historical information from a geographical survey collected in the mid-19th century. The study has been published in the journal Animal Conservation. It provides new information on the history of wolf declines due to human persecution.

More07.09.2022 | Media Release, sDiv, TOP NEWS

Location, location, location! What leads to lignification on islands

Based on a media release from Philipps-Universität Marburg. Marburg/Leipzig/Leiden. Increased drought, the lack of predators and isolation lead to a tendency of plants on islands to become woody. The location of the islands on which the species concerned are native also plays a role. This is the result of a study led by the Philipps University of Marburg and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) together with the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre in Leiden and other institutions. The study by the German-Dutch research team, which has now been published in the scientific journal PNAS, shows how islands act as natural laboratories of evolution.

More01.09.2022 | iDiv Members, Media Release, Research, TOP NEWS

High plant diversity is often found in the smallest of areas

Based on a media release by Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg Halle/Leipzig. The steppes of Eastern Europe are home to a similar number of plant species as the regions of the Amazon rainforest. However, this is only apparent when species are counted in small sampling areas rather than hectares of land. An international team of researchers led by the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig has now shown how much estimates of plant diversity change when the sampling area ranges from a few square metres to hectares. Their results have been published in the journal Nature Communications and could be utilised in new, more tailored nature conservation concepts.

More15.08.2022 | Evolutionary Ecology, Media Release, Science-Policy, Science-Policy, TOP NEWS

National parks – islands in a desert?

Leipzig/Jena/Bonn. How effective is biodiversity conservation of European and African national parks? This seems to be strongly associated with societal and economic conditions. But even under the most favourable conditions, conservation efforts cannot completely halt emerging threats to biodiversity if conditions outside of the parks do not improve. This is the conclusion of a new study led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI EVA), and the University of Bonn, in collaboration with the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), Leipzig University, the Friedrich Schiller University Jena and many other institutions. The study published in the journal Nature Sustainability highlights the urgent need for a better design of national park networks.

More27.07.2022 | Biodiversity Conservation, iDiv Members, Media Release, TOP NEWS

LifeGate – New interactive map shows the full diversity of life

Joint press release of Leipzig University (Botanical Garden) and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Leipzig. Researchers from Leipzig have published a gigantic digital map displaying the full diversity of life through thousands of photos. The so-called LifeGate encompasses all 2.6 million known species of this planet and shows their relationship to each other. The interactive map can now be accessed free of charge at lifegate.idiv.de.

More19.07.2022 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Informing future conservation priorities of ecosystems in the Tropical Andes